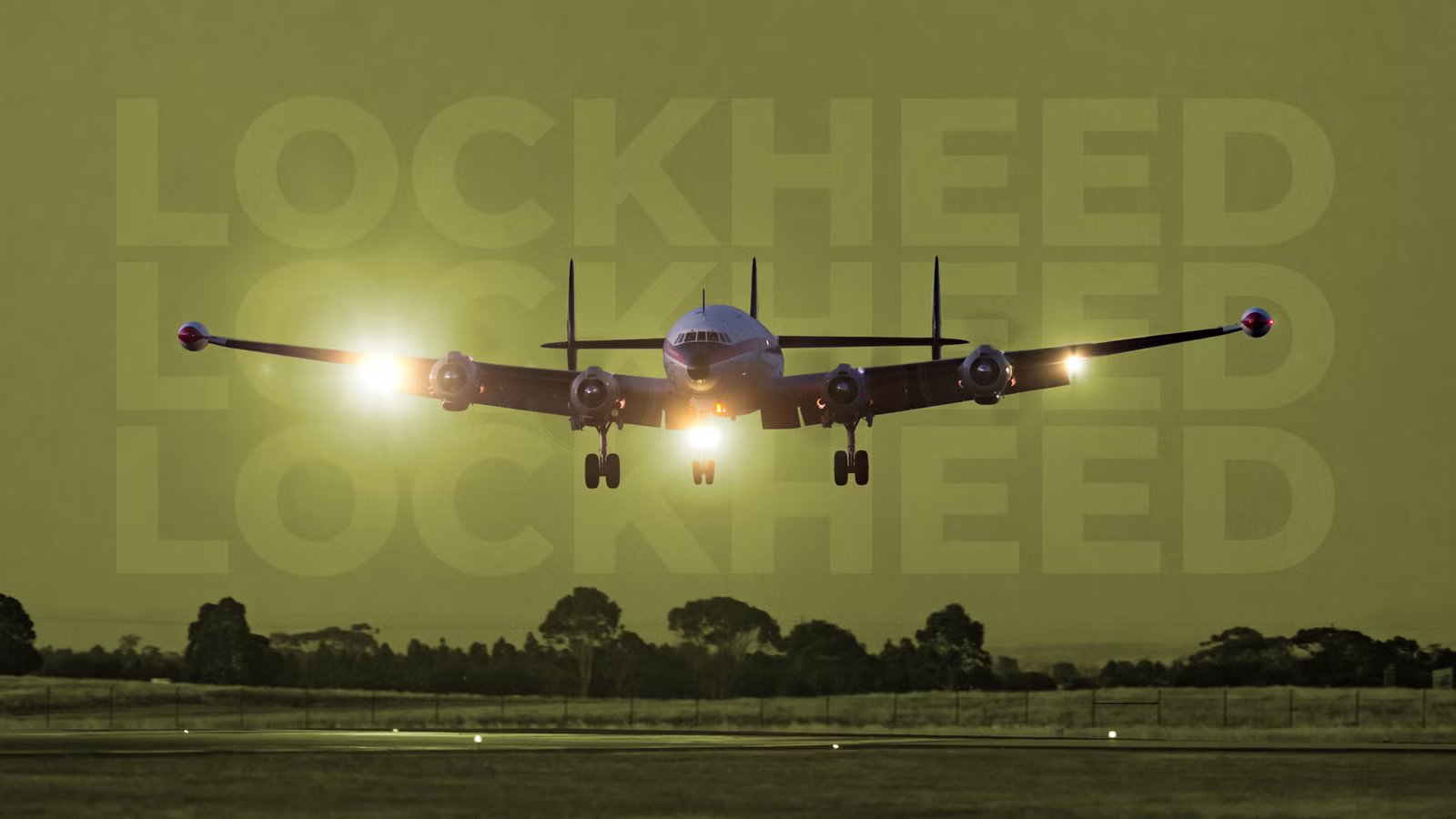

The Lockheed Constellation, affectionately known as the ‘Connie,’ is one of the most iconic aircraft of the golden age of aviation. With its triple-tail design, curvaceous fuselage, and powerful radial engines, the Constellation was a true milestone in the modern era of long-range air travel. But in 2026, how many of these jewels of aviation history remain airworthy? This article explores the last flying Lockheed Constellations, their importance, a brief history of the type, and how they continue to inspire aviation enthusiasts around the world.

From its origins in the 1940s as a military transport and commercial airliner to its retirement in the late 20th century, the Lockheed Constellation played a pivotal role in shaping global aviation. We’ll trace the aircraft’s development, its operational legacy, and the remarkable story of the last two airworthy examples. Along the way, we’ll examine what makes this aircraft so special, how it was saved from the scrapyard, and what it takes to keep it flying today.

The Two Airworthy Constellations

As of 2026, only two Constellations take to the skies under their own power. One is VH-EAG ‘Southern Preservation,’ operated by Australia’s Historical Aircraft Restoration Society. This C-121C Super Connie carries passengers on demonstration flights and features a fully restored Qantas livery. Based at Illawarra Regional Airport, it offers cockpit tours, charter experiences, and regular appearances at Australian airshows.

Meanwhile, N422NA ‘Bataan’ is maintained by the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino, California. This VC-121A served General Douglas MacArthur, NASA’s Apollo program, and theater commanders across the Pacific. After an eight-year restoration, it now flies at major US airshows, complete with period-correct VIP interior and vintage avionics. Together, these two aircraft preserve the engineering prowess, elegance, and historical significance of the Connie line, serving as flying museums that connect us directly to the dawn of pressurized, long-haul air travel.

History Of The Lockheed Constellation

In June 1939, at a discreet meeting in a Beverly Hills hotel, Howard Hughes and TWA president Jack Frye sat down with Lockheed’s top brass, including company president Robert Gross and chief engineer Clarence ‘Kelly’ Johnson, to discuss refining Lockheed’s proposed L-44 airliner. Their goal was ambitious: develop an aircraft that could carry 20 passengers in sleeper accommodations across the US nonstop, fly 100 mph (160 km/h) faster, and cruise 10,000 feet (3,048 m) higher than the reigning Douglas DC-3 .

Achieving this leap in performance required one key innovation: cabin pressurization. While Lockheed had already tested the concept on its experimental XC-35 in 1937, and Boeing’s 307 Stratoliner was the first pressurized airliner to enter limited service, it was the forthcoming Lockheed Constellation that would become the first pressurized aircraft to see widespread commercial use. TWA placed an initial $18 million order for the newly named L-049 variant Constellation.

Pan American World Airways followed suit, placing an order for 40 machines. However, despite the commercial enthusiasm, none of the aircraft would enter airline service before the end of World War II. The US government requisitioned all L-049s, converting them into C-69 transports for the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) during World War II, to ferry troops and supplies between the United States and Europe. During the wartime freeze on commercial flying, Hughes cleverly leveraged his influence to secure military cooperation.

This enabled record-setting and route-proving missions, ensuring TWA remained front-of-mind for the postwar aviation boom. Notably, Pan Am was initially restricted to operating its Constellations only on international routes, due to a prior exclusivity arrangement Lockheed had with TWA. In 1953, the L-1049 Lockheed Super Constellation, a lengthened variant equipped with a weather radar, entered service with TWA, Eastern Airlines, Air France, and ![]() Lufthansa.

Lufthansa.

After 1962, all military variants were designated as C-121. Military Connies fell into three broad categories: transports (C-69/C-121), VIP shuttles (VC-121), and airborne warning-and-control (RC-121/EC-121/WV-2).

Each variant retained the Connie’s pressurized cabin and high-speed cruise but received specialized equipment: cargo doors, weather radar, command-post consoles, or ASW/EW sensors, tailored to its mission. Over 600 military-configured Connies served US and allied forces from 1943 through the early 1970s, often side-by-side with emerging jet transports and AWACS platforms.

This Is The Oldest Lockheed Commercial Aircraft Still Flying

From the TriStar Stargazer to Buffalo’s Electras and Australia’s Connie — meet the oldest Lockheed commercial aircraft still flying today.

Technical Data

The Lockheed Constellation’s lasting appeal lies not only in its graceful lines but in the engineering feats tucked beneath its skin. By combining advanced pressurization, high-power radial engines, and aerodynamic refinements, Lockheed set new performance benchmarks that have defined propeller liner capability for decades. Early Constellation variants like the L-049 and Super Connie used four Wright R-3350 radial engines, each rated at 2,500 hp in normal form and boosted to as much as 3,400 hp.

The triple-tail configuration didn’t just become an icon. Rather, it allowed the aircraft to fit existing hangar doors without trimming vertical stabilizers. Cabin pressurization up to 4.75 psi meant cruising at 20,000–25,000 ft above most weather, while a wing redesigned with NACA-optimized sections delivered a top speed nearing 375 mph (603 km/h).

|

Specifications |

L-1049 Super Constellation |

|---|---|

|

Engines |

4 × Wright R-3350-PA-54 Turbo-Compound |

|

Power (per engine) |

2,500 hp (normal); 3,400 hp (boost) |

|

Wingspan |

123 ft 0 in (37.5 m) |

|

Length |

95 ft 2 in (29.0 m) |

|

Service Ceiling |

25,000 ft (7,620 m) |

|

Maximum Cruise Speed |

375 mph (603 km/h) |

|

Range (maximum ferry) |

7,551 nm (8,690 km) |

|

Fuel Capacity |

6,257 US gal (23,690 L) |

|

Cabin Differential Pressure |

4.75 psi (equivalent to 8,000 ft) |

|

Typical Passenger Load |

80–109 (Super Connie) |

Beyond raw numbers, understanding Connie’s operations offers insight into mid-century aeronautical practice. Pilots managed engine power with manual mixture and prop-feathering controls, balancing fuel economy against climb demands.

Meanwhile, flight engineers monitored intercooler temperatures on each turbo-compound system, a task that modern crews seldom encounter. For the enthusiast visiting an airshow, listening to the distinctive “whoosh” of exhaust recovery turbines or spotting original astrodomes used for celestial navigation provides a visceral link to the era when propliners pioneered the world’s first true jet-like routes.

What Makes ‘Southern Preservation’ Unique?

VH-EAG ‘Southern Preservation’ is the military variant of the iconic Lockheed Super Constellation, Originally built as a C-121C for the United States Air Force , this aircraft, with the serial number 54-0157 and construction number 4176, was delivered on October 6, 1955, and first assigned to the 1608th Military Air Transport Wing at Charleston Air Force Base, South Carolina. On July 25, 1962, it was transferred to the Mississippi Air National Guard, and later, on February 14, 1967, it moved to the West Virginia Air National Guard.

Here, it remained in service for the next five years. The aircraft’s final active assignment began in mid-1972 with the Pennsylvania Air National Guard, before being retired and placed into storage at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson, Arizona, in June 1977. After nearly two decades in the desert, the derelict Super Constellation was noted by some members of the Historical Aircraft Restoration Society (HARS) who were in search of Neptune spares (HARS currently operates the only flying Neptune in the world).

That was the start of a five-year-long restoration project, made up of 47 team trips from Australia to Arizona, that saw the HARS volunteers working for something like 16,000 hours. In September 1994, the Super Constellation was registered as VH-EAG and named ‘Southern Preservation.’ Two months later, it received a Qantas livery, and on February 3, 1996, it took off again, after 18 years on the ground, reaching Sydney after a 39.5-hour-long flight through Oakland, Honolulu, Pago Pago, and Nadi.

Today, VH-EAG operates from the HARS Aviation Museum in Illawarra Regional Airport. Its continued airworthiness is a unique achievement, made possible by a passionate community of engineers, aviators, and volunteers who maintain it to flying condition. The aircraft is often showcased at airshows across Australia, and apart from stirring nostalgia among older generations, it also introduces younger audiences to the elegance and complexity of piston-driven flight.

Why In The World Did Lockheed Martin Stop Producing Commercial Planes?

The Lockheed story is a reminder that in aviation, ambition must align with economic realities, or risk grounding even the mightiest flyers.

The story of VC-121A 48-0613, better known as ‘Bataan,’ begins in late 1948 when the newly formed US Air Force took delivery of ten L-749A Constellations outfitted for long-range transport missions. Designated C-121A, serial 48-0613 was quickly pressed into service with the Military Air Transport Service (MATS), hauling cargo and personnel from Westover AFB to Rhein-Main during the Berlin Airlift. In 1950, Lockheed converted 613 into a VIP shuttle.

This involved installing weather radar (the first USAF type so equipped), extra panoramic windows, and a sumptuous executive interior for 20–44 passengers. Renamed VC-121A ‘Bataan’ by General Douglas MacArthur, the aircraft carried him on 17 sorties over Korean battlefields and to his pivotal Wake Island meeting with President Truman, cementing its place in aviation lore. After MacArthur’s relief in April 1951, Bataan continued ferrying theater commanders across the Pacific.

Indeed, Generals Ridgway, Clark, Taylor, and LeMay were among those to have enjoyed the Constellation’s peerless blend of range, speed (up to 331 mph), and cabin comfort. Following its VIP tenure, ‘Bataan’ entered a second life with NASA from 1966 to 1970 under the tail code N422NA. As part of the Apollo Calibration Aircraft fleet, it carried blocks of tracking computers and telemetry gear to validate global communication stations supporting lunar missions.

When Apollo funding waned, the Connie was retired to the Army Aviation Museum at Fort Rucker, Alabama, where it languished outdoors for over two decades. In 1993, Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino, California, rescued the airframe, moving it to a climate-controlled hangar and periodically displaying it at their Valle/Grand Canyon facility. Though structurally intact, years of exposure left corrosion in the wing spars, and avionics long obsolete, relegating Bataan to static status while its storied history gathered dust.

The Bottom Line

Connies remain invaluable ambassadors of mid-century aeronautical progress, appearing in documentaries, hosting educational flights, and connecting generations through the shared wonder of piston-engine flight. Their thunderous takeoffs at airshows still draw crowds, reminding us how these propliners once redefined global connectivity.

For those eager to witness history in motion, both HARS and Planes of Fame publish annual flying calendars with public demonstration schedules. Enthusiasts can book cockpit tours and even scenic flights, while aspiring restoration volunteers gain hands-on experience working on original airframe components, engines, and avionics. This engagement fosters a living community of craftsmen, pilots, and historians dedicated to keeping the Connie spirit airborne.

Looking ahead, rising maintenance costs, evolving airworthiness regulations, and the retirement of veteran engineers will test preservation efforts. Success will hinge on partnerships between museums, educational institutions, and sponsors, honoring Connie’s legacy without compromising its authenticity. In this way, the last flying Connies may chart a course where innovation and heritage soar hand in hand.