This article is an onsite version of our Europe Express newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday and fortnightly on Saturday morning. Explore all of our newsletters here

Hallo from Berlin and welcome back to Europe Express.

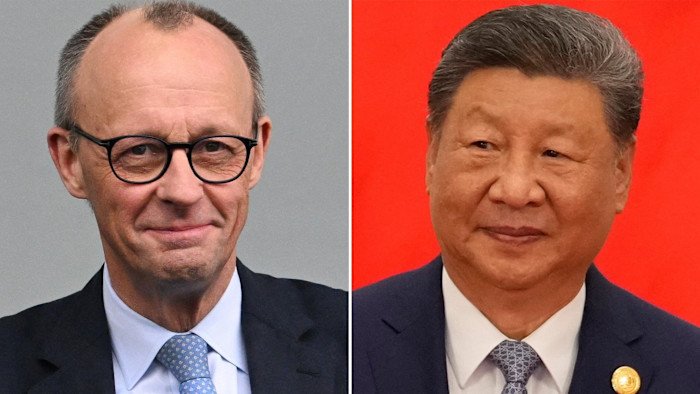

All (European) eyes will be on German chancellor Friedrich Merz next week when he heads to Beijing for his inaugural state visit to China.

While a string of security and trade crises emanating from Donald Trump’s US administration has preoccupied the conservative leader for most of his first year in office, China’s mounting economic challenge to Europe’s largest economy is becoming impossible to ignore. How Merz chooses to handle it will have far-reaching implications for the EU.

India first, China second

Germany’s export-driven success during the 2000s and 2010s was closely tied to China’s rise as a manufacturing powerhouse and a vast consumer market. That is why former conservative chancellor Angela Merkel chose Beijing for her first visit to Asia in 2006, travelling there twice as often as she did to Japan over her 16 years in office. As geopolitical tensions between Washington and Beijing later intensified, her social democratic successor Olaf Scholz opted to visit Japan first, China second.

Merz chose India first. By travelling to Beijing’s main economic rival in the region — shortly before the EU struck a free trade deal with New Delhi last month — he has signalled an intention to reduce Germany’s reliance on China at a time when deindustrialisation pressures are growing at home. “This was a conscious choice, which has not gone unnoticed in Beijing,” said an aide. Another said: “India is the future.”

Relations between Berlin and Beijing have become increasingly strained over the past year. Breaking with his predecessors, Merz entered office with open scepticism, warning German companies of the “great risk” of investing in the world’s second largest economy.

Germany’s deep dependencies were thrown into sharp relief last autumn, when China imposed sweeping restrictions on rare earth exports — vital to a number of products from cars to wind turbines and defence equipment. German carmakers later warned of serious manufacturing disruptions after Chinese-owned chipmaker Nexperia, which operates plants in Germany, threatened to halt supplies.

In October, Germany’s foreign minister Johann Wadephul, who had called Beijing to refrain from altering the status quo in the Taiwan Strait by force, abruptly cancelled a visit to China after tensions flared. According to a German government insider, Chinese officials declined to organise senior-level meetings and requested he visit a museum dedicated to Japan’s wartime atrocities. Wadephul eventually travelled to Beijing in December.

China’s intensifying industrial threat

Long the land of opportunities for German business, China has now turned into an existential threat for Berlin.

“While German manufacturers have grown more dependent on inputs from China, the importance of the Chinese market for German jobs and prosperity is declining,” writes Noah Barkin, an analyst at Rhodium Group.

This trend is accelerating. Rhodium estimates that German goods exports to China have fallen by 9.3 per cent last year to their lowest level in a decade — a 23 per cent decline below their 2022 peak. German car exports have dropped by two-thirds in the past three years. Last year for the first time, Germany ran a trade deficit in capital goods with China. Chinese competition is also biting in third markets.

German carmakers producing locally hope that new models will help stem their loss of market share in China. But, as Barkin notes, “it will primarily benefit jobs and value creation in China.”

At home, the picture is sobering: German industry is shedding jobs amid a surge in cheaper electric vehicles and steel redirected to Europe from the US market following Trump’s tariffs on Chinese goods. Germany’s industrial sector slashed about 124,000 jobs last year, according to estimates by EY.

Merz’s message to Xi

Against this backdrop, Merz is arriving in Beijing with a markedly tougher trade stance than previous German chancellors.

A longstanding defender of free trade in the Christian Democratic tradition, his inclination is to resist calls from Paris and other EU member states to raise protections, even in the face uncompetitive Chinese trade practices. But that was as long as the export model still worked in Germany’s favour.

The mood has shifted: In November Merz backed measures to shield the country’s struggling steel industry from cheap Chinese imports flooding the market.

According to one government aide, Berlin is now even “open to Buy European” — Brussels’ plan to prioritise European production in public procurement across digital and industrial sectors. The European Commission is expected to propose the Industrial Accelerator Act next week, which would set minimum European-content requirements for strategic technologies, such as renewables, batteries and cars in order to qualify for government subsidies. It would also require foreign investors to create local jobs under certain conditions.

Yet, despite this convergence with Paris, Merz — who is travelling to Beijing with a large corporate delegation — remains more cautious. He and his advisers insist that any Made-in-Europe measures should be tightly targeted at strategic sectors such as critical minerals, limited in duration and used only as a measure of “last resort”.

Part of the hesitation reflects the stance of major German companies, some of which are doubling down on China even as the chancellor urges de-risking. Even carmakers under pressure from Chinese rivals at home insist they still need access to the Chinese market — for innovation as much as for profits — and have urged Berlin not to escalate trade tensions.

Barkin sees in this caution the remnants of “a stubborn adherence to ordo-liberal principles that set hard limits on the state’s role in the economy. In an era when China and the United States, but also countries like Japan, are using the levers of government to reshape economic incentives, Germany risks being sidelined without a more pro-active approach,” he argues.

Still, advisers say that Merz will use his trip — closely coordinated with Paris and Brussels — to convince Xi Jinping to rein in industrial overcapacity that is flooding European markets and curb subsidies and other unfair competitive practices against foreign firms.

This message will come with a warning: If Beijing fails to act, Europe’s protectionist backlash — including from Berlin — should come as no surprise.

Last year, my colleagues Olaf Storbeck, Sebastien Ash and Florian Müller explored the decline of German industry.

Anne-Sylvaine’s picks of the week

Recommended newsletters for you

The AI Shift — John Burn-Murdoch and Sarah O’Connor dive into how AI is transforming the world of work. Sign up here

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Vital news and views on what central banks are thinking, inflation, interest rates and money. Sign up here