It was designed in the 1950s to be the world’s first “drive-through shopping centre”, a futuristic structure with more than than two miles of ramps looping past 300 shops, as well as cinemas, a hotel, a private club, a concert hall and a heliport.

But the building was never completed, and under the regimes of Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro, spaces envisioned as shops were turned into cells, and El Helicoide became Venezuela’s most notorious torture centre for political prisoners.

Now, under US pressure, acting president, Delcy Rodríguez – who previously oversaw the prison as Maduro’s vice-president – has announced plans to shut down El Helicoide and turn it into a cultural centre.

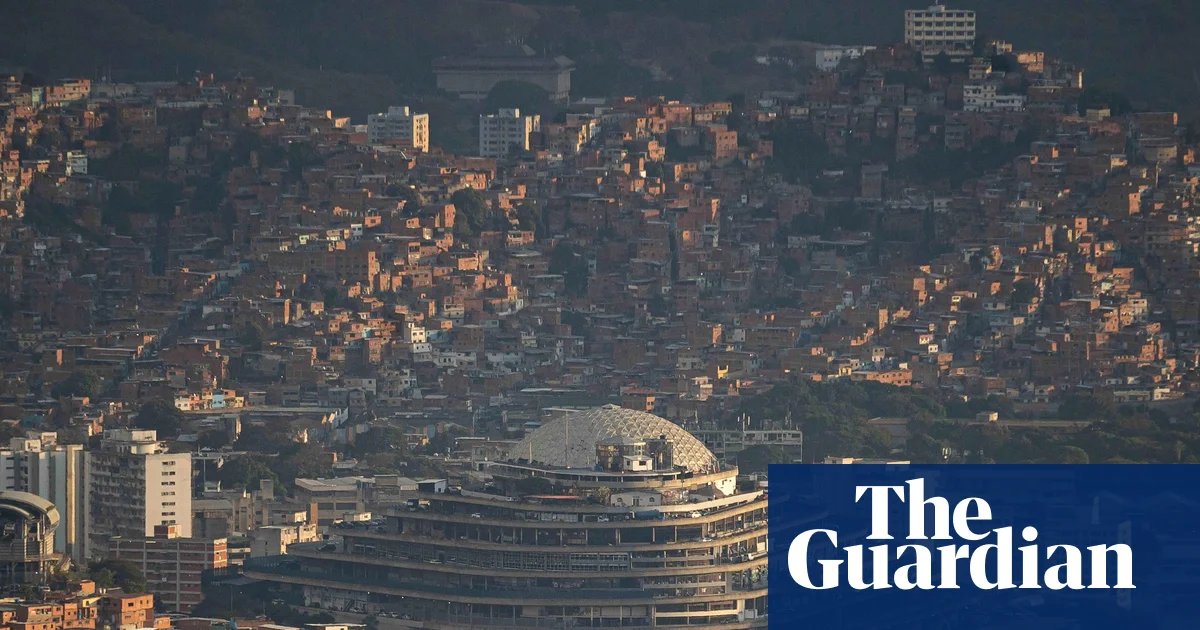

The giant structure, which looms over central Caracas, will be turned into a “sports, cultural and commercial centre for police families and neighbouring communities”, Rodríguez said on Friday.

The move is part of a raft of measures touted by Rodríguez as proof that the government has turned the page since Maduro was captured and renditioned to the US. But activists have criticised the plan as an attempt to rehabilitate a symbol of Venezuela’s collapse – and erase the regime’s long history of repression.

“The horrors committed at El Helicoide have already been sufficiently documented and exposed by numerous human rights organisations and by a United Nations mission,” said Martha Tineo, coordinator of the NGO Justicia, Encuentro y Perdón (Justice, Encounter and Forgiveness, or JEP), one of the groups that have for years supported political prisoners and their families.

“We welcome the fact that it will be shut down – but not so that it can be turned into some kind of social or recreation centre,” Tineo said.

Activists argue the site should instead be turned into a space of memory, along the lines of the former Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada (Esma) in Buenos Aires, a torture centre under Argentina’s military dictatorship which is now a museum. That would offer “a form of reparation for victims by telling the truth and ensuring that these horrors are not repeated”, Tineo said.

Named after its spiralling, brutalist concrete structure, the building was conceived in the 1950s to project an image of modernity fuelled by oil wealth during the military dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jiménez, but it was abandoned after he was overthrown in 1958.

In the 1970s it became a temporary shelter for thousands left homeless by devastating landslides, but the overcrowded structure soon became notorious for drug trafficking and crime. In the 1980s, the families were moved out, and it was used as the headquarters for the domestic intelligence service.

Under Chávez, El Helicoide became a detention centre for political prisoners held by the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (Sebin).

Repression intensified under Maduro, and reports documented practices of torture including electric shocks, beatings, suffocation and prolonged bans on family visits. In recent years, El Helicoide and Sebin were under the direct command of Rodríguez.

Engineer and activist Angel Godoy, 52, spent nine months in El Helicoide last year. Although he says he was not tortured there, he was unable to contact his family for the first three months.

He was arrested in the regime’s crackdown after the opposition organised a nationwide effort to collect voting records and prove that it had won the 2024 election – even though Maduro nevertheless declared himself the victor.

His organisation had trained citizens to monitor the electoral process. “They saw this as a major threat and came after us,” said Godoy, who was charged with terrorism, incitement to hatred and to armed action.

Three months ago, he was transferred from El Helicoide to Yare prison, which is also notorious for its overcrowding and dire conditions. When he was released on 14 January, after 372 days behind bars, Godoy left behind all his few belongings for his cellmates: sandals, a toothbrush, toiletries and some food.

“When the guards shouted my name, my fellow inmates began shouting, ‘Freedom, freedom!’ As I walked out, they told me to fight for them and not to forget them,” Godoy said.

Like dozens of others released since the US attack, Godoy was not granted full liberty: although, unlike others, he has not been barred from giving press interviews, he must still report to court every 30 days and is prohibited from leaving the country.

Activists estimate that between 600 and 800 political prisoners remain behind bars, even after Rodríguez announced her intention to send an “amnesty” bill to congress.

“I think I will only truly be free when each and every one of my fellow prisoners is out of those unjust cells,” Godoy said.

While no date has been set for a vote, the bill is expected to pass easily in the national assembly, which is dominated by regime loyalists.

A main concern of activists is that, according to the acting president, those convicted of crimes such as homicide will be excluded. Yet among political prisoners are many accused of never-proven allegations of supposed assassination plots against Maduro.

JEP’s coordinator, Tineo, also argues that these people must be compensated for being wrongfully imprisoned for crimes they did not commit, and that political prisoners, former detainees – many of whom died in custody – their families and civil society organisations must take part in the discussion of the amnesty bill.

A new oil industry law, approved last week, has drawn the same criticism over a lack of transparency and public debate, reinforcing the view among critics that Rodríguez’s administration represents a form of Chavismo 3.0.

“Trying to carry on as things were in the past would amount to confirmation that there is no real will for change from the government,” Tineo said.