![]()

The title of this post comes from a subhead in Thomas De Zengotita’s book, Mediated: How the Media Shape the World Around You (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2005) in which the author writes about choices, and “how much the screen of human consciousness can register at a given moment.” This is an important question for today, with so many people (younger people, especially) glued to their phones, always online, always engaged, always scrolling, clicking, texting. And scrolling past the headlines, not reading the whole story, getting only a few words before scrolling on to the next headline or jumping to another source or site. Doomscrolling isn’t just a satirical neologism: it’s a way of life today.

The title of this post comes from a subhead in Thomas De Zengotita’s book, Mediated: How the Media Shape the World Around You (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2005) in which the author writes about choices, and “how much the screen of human consciousness can register at a given moment.” This is an important question for today, with so many people (younger people, especially) glued to their phones, always online, always engaged, always scrolling, clicking, texting. And scrolling past the headlines, not reading the whole story, getting only a few words before scrolling on to the next headline or jumping to another source or site. Doomscrolling isn’t just a satirical neologism: it’s a way of life today.

Not only are there vastly more competing media sources available today, they all have a presence online, they all have volume, they are all clamouring for attention, and they all have equal presence on social media — without moderation to identify their credibility or political leaning. There is usually no way for users to identify which are reliable, which are credible, which are ideological rather than factual. Far-right propaganda outlets (some promoting Putin’s agenda) like Fox Newz and Newzmax are easily confused by gullible readers with actual, credible news sources. And an Oort Cloud of independent commentators, podcasters, and broadcasters offers a wide range of alternate views and opinions on any- and everything, often without any substantial qualifications for having their opinion. Some of whom have become very rich milking the social media markets (look at the rage-baiting racist hatemonger Charlie Kirk, for one example).

The ubiquitous persistence of choice in every field is presented to us as the benefit of a marriage between democracy and capitalism. Choice, we’re told, equates with freedom. And don’t we all want choice? To be able to choose our elected representatives, the political party we support, the gods we worship… but also the kind of vehicle we drive, the food we eat, the place where we live, the jobs we do, the careers we pursue, the things we own, our pets… that’s the story we’re told over and over: more is better. We’re free to choose everything (unless you’re a woman living in a US MAGA or fundamentalist Islamic state). More choice means we can live more satisfied lives. Or so the theory goes.

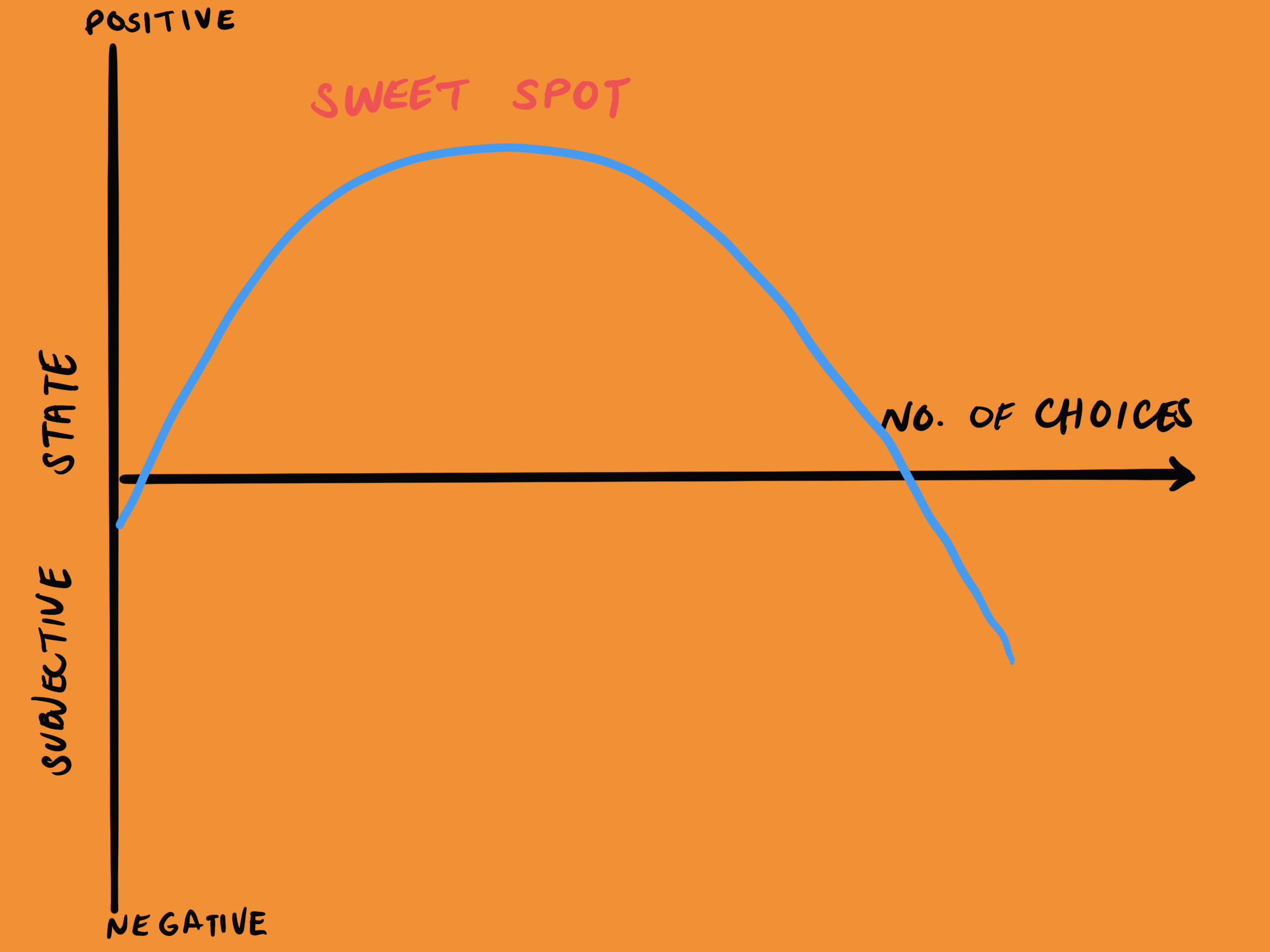

But when does choice become too much? When do we stop seeing more choices as a boon and start feeling it a drudgery to comb through them all, trying to decide which to select? Can more become less? Can too much choice be a burden rather than a freedom? I think so.

But when does choice become too much? When do we stop seeing more choices as a boon and start feeling it a drudgery to comb through them all, trying to decide which to select? Can more become less? Can too much choice be a burden rather than a freedom? I think so.

Just trying to find the right product online can be a frustrating experience. I can seriously consider, say, window blinds or rice cookers in a retail store where space is limited by physical size, so the choices are few. But online, often with the number of products in any search numbering in the hundreds or even thousands on sites like Amazon, considering each one, reading reviews, noting and comparing specifications — on paper, ironically, since few sites have an online way to compare products by specs and review rating — is confusing and often leads to indecision. And just to make it more challenging, there are many online sites selling the same or similar, competing products, and the reviews of those products are often quite different from the reviews on competing sites. And then come the frequent emails with the subject line, “We found something you might like…” with even more choices.

Can you really trust online reviews these days? I am skeptical of many, if not most. How can you tell if they are real (made by actual disinterested consumers using the product or service) or scams (created by the sellers or their competitors)? How can you tell if they were created by AI in paid bot farms, sold in bulk by review brokers?

A single AI-powered review farm can flood Amazon, Yelp, Google, and Trustpilot with fake testimonials—making it nearly impossible for consumers to distinguish real from fake.

That’s part of the message in the book, The Paradox of Choice, by psychologist Barry Schwartz. It is subtitled “How the Culture of Abundance Robs Us of Satisfaction.” In a TED Talk, he said that the official dogma of all Western industrial societies is, “If we are interested in maximizing the welfare of our citizens… maximize individual freedom. …The way to maximize freedom is to maximize choice.” Well, not all Western nations have the pursuit of “freedom” as their main tenet or have it as blatantly spouted as in the USA, but as a core value it is generally part of the warp and weft of modern democracy. We want at least some freedom to choose pretty much everything in our lives. And, we’re told again and again, freedom to choose is an inalienable right.

That’s part of the message in the book, The Paradox of Choice, by psychologist Barry Schwartz. It is subtitled “How the Culture of Abundance Robs Us of Satisfaction.” In a TED Talk, he said that the official dogma of all Western industrial societies is, “If we are interested in maximizing the welfare of our citizens… maximize individual freedom. …The way to maximize freedom is to maximize choice.” Well, not all Western nations have the pursuit of “freedom” as their main tenet or have it as blatantly spouted as in the USA, but as a core value it is generally part of the warp and weft of modern democracy. We want at least some freedom to choose pretty much everything in our lives. And, we’re told again and again, freedom to choose is an inalienable right.

Schwartz warns that the “more options we have, the less satisfied we feel with our decision. This phenomenon occurs because having too many choices requires more cognitive effort, leading to decision fatigue and increased regret over our choices.” As the Decision Lab writes about it, “When the number of choices increases, so does the difficulty of knowing what is best. Instead of increasing our freedom to have what we want, the paradox of choice suggests that having too many choices actually limits our freedom.”

(There’s an irony here: in the USA where freedom of choice is so loudly touted, there are only two political parties from which to choose, one far-right authoritarian, one centrist-right, with no actual leftwing or alternative party available to voters).

(There’s an irony here: in the USA where freedom of choice is so loudly touted, there are only two political parties from which to choose, one far-right authoritarian, one centrist-right, with no actual leftwing or alternative party available to voters).

Choice also encourages consumerism because exercising your ability to choose makes a statement about yourself and your freedom. In his book, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, author Yuval Noah Harari wrote, “Consumerism sees the consumption of every more products and services as a positive thing. It encourages people to treat themselves, spoil themselves, and even kill themselves slowly by overconsumption.”

Excess choice can also have serious consequences. When Ontario Premier Doug Ford opened beer and spirit sales to all supermarkets and convenience stores in 2024, it seriously hurt LCBO sales, which translates to workers not being hired or even let go at various stores. It meant less revenue for the province (falling below $2 billion for the first time in a decade). And, to make up for the revenue loss, the LCBO has raised prices on many products.

That move also seriously hurt sales at the Beer Store outlets. This was originally announced at a cost of $225 million to taxpayers for the broken contract, but quickly ballooned to $612 million. The Beer Store has already closed more than 100 outlets as a result of revenue loss. Not only did this affect the employees who were laid off, but in many communities, the Beer Store was the major, sometimes the only, place where consumers could return empties for a refund. That means more empties are going into landfills and not being recycled.

The liberalization of alcohol sales — i.e. more choices for consumers — has also led to an increase in impaired (DUI) driving charges:

Since the liberalization, there has been a notable rise in impaired driving incidents, with police laying about 78,480 total charges and short-term suspensions per hour for alcohol or drug-impaired driving. This amounts to an average of 215 impaired-driving sanctions per day. The increase in charges is a direct result of the expanded alcohol sales, which have contributed to a growing problem on Canadian roads.

Last week, while shopping for food, I tried to count all the varieties and brands of dry rice in a local grocery store (these pictures are from that shopping trip). Just in the international foods section, there were almost 90, the great majority of them brands from India (with several from Pakistan, plus a few Thai, Japanese, and Vietnamese); with one exception, they were all brands we are not familiar with. There were dozens of just basmati rice choices. The labels of some packages showed us there are several different types of basmati rice, but there was no way for us to identify which was best for our needs. I had to look this up online to find out how little I really knew about basmati rice, a product I’ve been eating for decades.*

While I always enjoy an opportunity to learn about almost anything, in the grocery store, and am a somewhat obsessive label reader and comparison shopper, faced with so many choices, I was just bewildered. How do I choose?**

That count doesn’t include the Uncle Ben’s rice and its competitors shelved in another aisle of the store (the final photo), or the choices between pre-cooked rice available in dozens of flavours and styles and various premade meals with rice as an ingredient. And how does a consumer choose which brand to buy? There are no guides, no tasting or cooking notes on the shelves. There are no codes to indicate the quality or the reliability of the brand or even which of the many varieties are in the package.

That count doesn’t include the Uncle Ben’s rice and its competitors shelved in another aisle of the store (the final photo), or the choices between pre-cooked rice available in dozens of flavours and styles and various premade meals with rice as an ingredient. And how does a consumer choose which brand to buy? There are no guides, no tasting or cooking notes on the shelves. There are no codes to indicate the quality or the reliability of the brand or even which of the many varieties are in the package.

Yet this seemingly large number of rice choices pales in comparison to the sheer number of choices of “book nooks” on Amazon (more than 800). This is what social historians call a democracy of consumption; it assumes that the marketplace will sort out the winners and losers by consumers voting with their wallets (or credit cards). And, according to that view, eventually the number of “book nooks” will diminish to the few “winners” that are actually popular with consumers.

Bloggers Kasurian and Ahmed Askary wrote that,

This is democracy as consumer sovereignty, which grants the freedom to choose among an abundance of goods, services, and lifestyles. In market societies, the shopping mall and the ballot box have become companion institutions, each promising a form of empowerment that flatters the individual as the ultimate arbiter of value. For many citizens of prosperous nations, the freedom to consume has become indistinguishable from freedom itself. In some cases, it has superseded political liberty entirely.

This substitution is not merely a curiosity of authoritarian development models. It has penetrated Western democracies themselves, where the citizen-as-consumer has gradually displaced the citizen-as-producer. The distinction matters. A producer contributes to the common stock of wealth through labour, investment, or enterprise; their relationship to the polity is one of mutual obligation. A consumer draws upon that stock; their relationship to the polity is one of entitlement. When producers predominate in a democracy, politics tends toward questions of investment, infrastructure, and institution-building, toward the conditions of future prosperity. When consumers predominate, politics tends toward questions of distribution, transfer, and immediate gratification, toward the division of existing wealth.

Shopping is, of course, about a lot more than just choice. As numerous studies and research reports have documented, shopping is a complex activity that involves much more than satisfying mere need and want: it includes status, curiosity, psychological and social effects, political decisions (like patriotic Canadians boycotting USA-made products and services), how well informed the consumer is, cost and perceived value, taste, peer pressure, product comparisons, social influence, seasonal influences, dopamine, perception of success, pleasure, anxiety, fashion, appetite, and much more. ***

In his book, You May Also Like: Taste in an Age of Endless Choice, author Tom Vanderbilt writes, “Where economists tend to think that a choice ‘reveals’ a preference, psychologists often suspect a choice creates the preference.” That is, are we choosing what we want or wanting what we choose? Buyer’s remorse is often kept secret. People sometimes defend their choice of product, service, or politician loudly because to admit it was a wrong decision, for many people (not just men!) is to admit failure. That failure can call into question your judgment and your intelligence.

This adage applies to politics equally as well as it does to consumerism. Which is why, I suspect, so many MAGA followers continue to support the deranged dictator in cognitive decline making overtly racist posts on social media, making overtly misogynist attacks on female reporters, making erratic and harmful policy decisions, devastating the USA’s democracy, acting illegally, grifting the nation to engorge his and his family’s personal fortunes, and lying about his involvement with the pedophile Jeffrey Epstein. To admit they were wrong about electing a convicted felon would make the voters look stupid and gullible.****

Would we, as consumers, be content with fewer choices? Perhaps: but it all depends on circumstances and what we are reducing. I am quite content with having one bin of Brussels sprouts and one bin of English cucumbers in the grocery store. But I would chafe at a similar reduction of choices in, say, hot sauces, or bread. Most of the automobile models — and even manufacturers — I will never consider (let alone afford), so their loss would not affect me. But I would be devastated by a similar loss of authors from bookstore shelves. MAGA cultists and their Maple MAGA counterparts are outraged that anyone speaks anything other than English; to me, nations would be much poorer without the music, the poetry, the cultures, the literature that sprang from other languages. Others may feel different, but how many people will seriously argue we need more than 800 choices in “book nooks”?

Ah, human felicity! to have at once so many wants suggested and supplied!

Letitia Elizabeth Landon, Romance and Reality, (1831) Volume I, Chapter 10

Notes:

* According to the blog at swayampaak.com, there are 11 main types of basmati rice:

- Basmati 370 (Pak Basmati)

- Basmati 385

- Basmati Ranbirsinghpura (R.S.Pura)

- Pusa 1121

- Pusa 1718

- Pusa 1509

- PK 385

- Super Kernel Basmati

- D-98

- Heirloom Basmati

- Brown Basmati

There is also a specialty, prized type, called Doongar Basmati, from the foothills of the Himalayas in the Doon Valley. The PK 385, Super Kernel Basmati, and D-98 are all from Pakistan, the rest from India. Hindgate.com has another list of popular basmati rice varieties:

- 1121 Basmati Rice – Extra-long grains, ideal for premium biryani.

- 1509 Basmati Rice – High yield, fluffy grains, widely exported.

- 1718 Basmati Rice – Strong aroma, excellent visual appeal.

- Pusa Basmati Rice – Light, fragrant, preferred by restaurants.

- 1401 Basmati Rice – Good cooking length and aroma at competitive pricing.

- Sharbati Basmati Rice – Affordable alternative with mild fragrance.

- Traditional Basmati Rice – Classic short fragrance, premium category.

It also lists 11 varieties of non-basmati rice. Aside from the popular basmati, there are other types of rice sold in India, including Sona Masoori, Kolam, Parboiled, Red, Black, Gobindobhog, Matta (Kerala Red), Indrayani, and Jeera Samba. Parboiled is also called converted rice, the type sold by the familiar brand, Uncle Ben’s. The Times of India lists ten popular types: Basmati, Sona Masoori, Pooni, Red, Black, Ambemohar, Jeerakasala, Kolam, Samba, and Navara. My search engine tells me that India has 200,000 rice varieties, including over 1,600 officially released cultivars, 154 hybrids, and thousands of local and regional types, although this site says “only” 6,000 varieties (and describes Dubraj, Bamboo, HMT Kolam, Mogra, Jasmine, Wild, Mapillai Samba, Indrayani, and several other varieties of rice). And after some hours of reading down this particular rabbit hole, I understand better not only why there are so many choices, but where they originate.

Some time ago, we found a brand that we liked among the many on offer by talking to other shoppers who recommended it. Unfortunately, that particular brand was no longer on the store shelves, at least not when we were shopping. Our current choice, by the way, was Tilda brown basmati, which we have also had in precooked packages and enjoyed. Armed with more information about rice, and maybe a printout or two to help, next time we need some, I will be label-reading intensely. Does anyone local sell Doongar?

** The LCBO (Liquor Control Board of Ontario) has brief tasting and entertaining notes on the bin tags for most products to help consumers choose the appropriate wine or spirit. Some beers and ciders are also labelled with such notes. While this information may not convey the full sense of the product, it does help consumers make a choice from among thousands of competing products. However, in my experience, it is equally important to read the sugar content listed on the bin tags. Even so, the buyer’s personal taste may not agree with the writer of the description; that highly-praised, award-winning wine may not taste so good when uncorked at home.

*** Choice, shopping, consumerism, decision making, and affluenza all interest me and seem related:

**** Many people vote along party lines, rather than through a considered choice of candidates based on their platforms, policies, and background. In some areas, this may in part be because there is no local media to interview candidates thoroughly. Or it may be that ideologically biased media praise or condemn candidates along party lines and their audiences vote accordingly.

As the Kasurians wrote, “The liberal ideal of democracy rests upon a particular vision of the citizen: informed, engaged, and capable of self-government.” But in Ontario’s most recent provincial election, only about 40% of the electorate bothered to vote, which meant a government elected by a mere 22% of the electorate. In the subsequent municipal elections, locally and across most of Ontario, about the same percentage of the electorate voted for municipal representatives. Those low turnouts suggest not only laziness, but ignorance on the part of voters. A call for voters to pass a basic civics test to prove they know enough about politics to make an informed choice has gone unheeded. As have calls for candidate politicians to be required to pass the same test. I support a mandatory voting system like that in Australia, where not voting carries a financial penalty added to tax returns.

Words: 2,918