Richard Baker’s approach to dealmaking and retail building has been to move fast, never overpay, throw it all against the wall, and see what sticks.

Not much did.

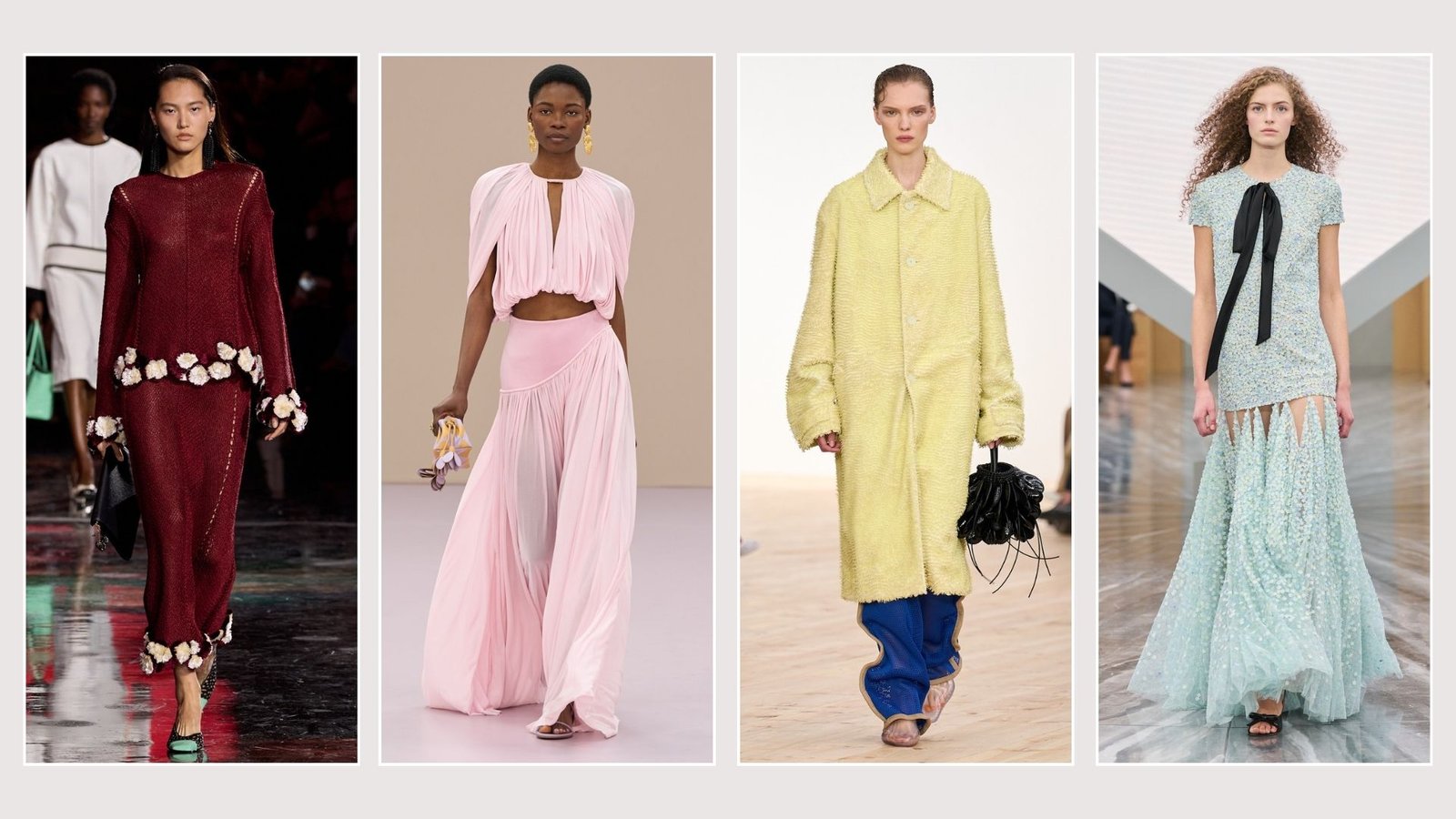

Baker’s vision of building and helming a luxury retail empire, putting Saks Fifth Avenue, Neiman Marcus, Bergdorf Goodman and Saks Off 5th all under the Saks Global corporate umbrella, came crashing down last January when the retail conglomerate filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Scores of vendors are owed millions of dollars after being stiffed for several years, even while Baker and his team gave assurances that all would work out and that the combination of Saks and Neiman’s would eventually thrive. Bills were unpaid, sources said, even as Baker continued to fly on a private plane and took his wife to fashion shows in Paris.

It was the latest in a string of retail bankruptcies that occurred while Baker controlled them — including Canada’s iconic department store Hudson’s Bay, which was liquidated and Fortunoff’s which was largely liquidated — or soon after he sold them off. Lord & Taylor went bankrupt shortly after Baker sold it to Le Tote, and Kaufhof in Germany went bankrupt after Baker sold it to Signa Corp.

Baker made millions from much of the retail real estate before selling the chains, and to be fair, there were years when Saks Fifth Avenue, as well as Hudson’s Bay and Lord & Taylor, under Baker’s control showed sales and profit gains.

Baker’s NRDC Equity Partners, controlled by Baker, his son Jack, along with partners William Mack and Lee Neibart, bought Saks in 2013, Hudson’s Bay and Fortunoff’s in 2008, and Lord & Taylor in 2006, which marked Baker’s entry into retailing.

Some of Baker’s ideas were half-baked. Hundreds of thousands of dollars were spent on plans to build an office tower atop the Lord & Taylor flagship, only to abandon the project to focus on the retail business itself. Saks licensed the Barneys New York brand from Authentic Brands Group, a deal touted as an opportunity to bring Barneys back to the retail landscape. But there was never much of a rollout beyond Barneys departments inside the Saks Fifth Avenue flagship in Manhattan and store in Greenwich, Conn. He even proposed creating a casino on the upper, underutilized levels of the Saks Fifth Avenue flagship.

At the opening of a Lord & Taylor in Boca Raton, Fla., in 2013, far from L&T’s store concentration in the north, Baker told WWD, “This could be the lifestyle shopping-center anchor for the future.” And as he stood at the entrance, a woman asked him why the store didn’t carry childrenswear because she was looking to buy gifts for her visiting grandchildren, to which he turned to an L&T merchant next to him and said, let’s do a private label children’s line. It never materialized.

Perhaps in his most unorthodox maneuver, Baker split the store and e-commerce operations of Saks Fifth Avenue, Hudson’s Bay and Saks Off 5th into separate companies in 2021, hoping to capitalize on the boom in e-commerce that occurred due to the pandemic. Insight Partners made a $500 million minority equity investment in Saks’ e-commerce operation, funding improvements in the website and its technology, and raising speculation of taking that business public. That never happened and the strategy at Saks Fifth Avenue and Hudson’s Bay was subsequently reversed.

At least $250 million was spent over four years renovating the Saks Fifth Avenue flagship, which relocated cosmetics to the second floor; opened up space for designer accessories and leased luxury shops, and moved ultra fine jewelry to a stylishly redesigned lower level. A flashy, color-changing Rem Koolhaas-designed escalator linking levels one, two and three was installed.

Opinions were mixed. Some saw the renovation as a daring and welcomed modernization defying department store norms. But certain beauty industry executives were upset because they saw their brands becoming less productive than they were on the main floor, once a beehive of activity. Some believe the transformation took the heart and soul out of an iconic, historic Fifth Avenue retail landmark.

Monetizing Real Estate

Baker is one of the most complex and unpredictable executives to disrupt the retail/fashion industry. His boyish appearance belies his dealmaking skills and ability to see the hidden value in retail real estate others overlooked. While unwinding weakened retail operations, Baker successfully monetized much of the retail real estate. In January 2011, Target Corp. acquired the leasehold interests in about 200 Zellers stores, which were part of Hudson’s Bay Co., for 1.8 billion Canadian dollars. In 2017, HBC sold the Lord & Taylor Fifth Avenue flagship building for $850 billion, not far off the $1.1 billion Baker’s private equity firm paid for the entire business.

“The truth is, back in 2006 when we bought Lord & Taylor, we were intrigued by the real estate. But once we got more involved, Richard saw the benefits of the operating business,” Neibart told WWD years ago.

Baker has capitalized on other retail real estate in Canada and Europe, including huge Hudson’s Bay flagships in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver, and mortgaging the Saks Fifth Avenue flagship as an important financing asset. Baker’s HBC bought German retailer Galeria Kaufhof in 2016 for 2.6 billion euros and sold it at a handsome profit to René Benko’s Vienna-based Signa Group for 3.8 billion euros in 2019, leading to the merger of Kaufhof and Signa’s Karstadt retail business to form Galeria Karstadt Kaufhof. Baker was back in Germany in 2024 when NRDC acquired the bankrupt Galeria in Germany.

Baker has never overpaid on a deal. He’s bought retailers at discount, though they were all past their prime. For example, the Neiman Marcus Group was purchased for $2.7 billion in December 2024 from a consortium of private equity firms and investment funds, which in 2020 spent about $5 billion to take over the business by eliminating $4 billion in debt and providing $750 million in financing to exit bankruptcy.

The 60-year-old Baker grew up in Greenwich, Conn., where at age 15 he started a catering business after attending culinary classes. He studied hotel management at Cornell University. Hospitality could have been his career, but he joined his late father’s real estate development business, which was focused on shopping centers, particularly strip centers. The young Baker was instrumental in attracting Walmart to many of the family’s strip centers.

Years later, Baker branched out from strip centers, seeing an opportunity in the high-end department store business. He formed a fund — NRDC — to buy businesses, an idea that came from his wife. “We were out with a bunch of friends in the private equity and hedge fund business, and later my wife told me that I was just as good as those guys and I could do just what they were doing. I woke up the next morning and said to myself, maybe she’s right.”

He targeted heritage brands with a real estate component and highly focused on either luxury, the midtier or off-price.

Risky Business

“I’m clearly an entrepreneur. I started in business at a young age,” Baker once told WWD. “The first chunk of my career was developing real estate. I like building businesses.…I think I get involved in the very big picture and very little details, not in the middle. What brands are we going to sell, what people are getting hired, I want to understand that. The execution in the middle, we have people for that.” He also cultivated a philanthropic profile, having established the Saks Fifth Avenue Foundation, which has raised millions for mental health awareness and programs, even as vendor bills went unpaid.

Baker had his sights set on Saks Fifth Avenue long before the company was in play. Ultimately, HBC bought the luxury retailer for $2.9 billion in late July 2013. It was typical Baker. He plays the retail game like a chess match, knowing what moves he will make well in advance of actually making them. When he bought L&T, he knew he was going to buy Saks and Neiman’s and was never private about his intentions. Not long after he bought L&T, he made an offer to buy Saks, but the Saks board issued a poison pill. It took another eight years to buy the rival retailer.

He’s got the stomach for large, risky deals and has been described as conceptual, more than practical, and tenacious. “He’s the kind of visionary who has his next actions already thought through. You want to be part of a path-breaking company,” said Gerald Storch, at the time serving as chief executive officer of Baker’s retail portfolio when it included Saks, Lord & Taylor and Hudson’s Bay.

Baker, himself, has acknowledged he moves fast and is not one to sit still. “I can’t read a book,” he once told WWD.

He’s been described as hands-on, decisive, a quick study who moves from subject to subject. While some CEOs can go on and on in meetings, “With Richard, it’s 20 minutes and you’re out of there,” one source told WWD.

By growing up in his family’s real estate business, not retailing, and by virtue of his style of conducting business, Baker has been in a class of his own, outside the circle of giant retail merchants like Allen Questrom, Terry Lundgren and the Nordstroms. They manage retail corporations with traditional operations and omnichannel strategies, whereas Baker was immersed in striking up deals, integrating acquisitions and raising money.

He’s been dogged by skepticism that he was never qualified to be CEO of a big retail company given his real estate background. Baker once said, “We are a global business that focuses on operating retail companies, acquiring and managing real estate, and mergers and acquisitions. It’s a company that has three major focuses.…Getting deals done? That’s the easy part. It’s what comes after the deal — building a new team, consolidating and executing the business for growth — that’s hard.”

Baker has been compared to Eddie Lampert. Both swooped up retailers with undervalued real estate intending to turn around the retail operations. He’s also compared to late Robert Campeau, the Canadian real estate executive who swooped up Federated Department Stores including Bloomingdale’s, only to drive it into bankruptcy. Like Campeau and Lampert, Baker took a lot of heat from the media. “He was good at shrugging off criticism,” the source said. “If there was something negative in the media, he would say don’t worry about it.”

At the 2017 WWD CEO Summit, just after disclosing the deal to sell the Lord & Taylor flagship, Baker said, “Being a retailer, that is too tough. Man, that is tough.” Regarding the real estate business, “that’s not as tough. It’s a place where we can make a lot of money.”

“Richard came into this business thinking very differently, He’s outside-the-box thinker,” said an executive who once reported to Baker. “He’s an idea guy. He asks a lot of questions, and he was always very generous with me. He was a great boss, super innovative, very approachable. A regular guy, and always with ideas.”

Selling Target the leases of Zellers in Canada, which was part of HBC, was “masterful,” the executive said. “Nobody was better at selling than Richard. He was inspirational. He was about innovation. He talked big picture. He got people to believe in his vision. Unfortunately he didn’t execute well. Did he have the right leadership for all of this? Yes. I’m upset about seeing Saks Global closing [certain] Saks, Neiman’s and Off 5th stores, but it’s easy to blame the person running the company. What about all the other people? The people in the company who can see on a daily basis what’s going wrong with the execution, the CFOs? I’m very thankful for having worked with Richard. I learned a lot from Richard — 100 percent. I don’t think the downward spiral of Saks Global can be pinned on just one person.”

The Work Around

Former Lord & Taylor workers suggest that Baker wanted its retail operations to succeed and wasn’t purely interested in its real estate. There were investments upgrading jewelry by partnering with the former Finlay Fine Jewelers, which operated leased fine jewelry departments. He brought a SaraBeth’s restaurant to Lord & Taylor, a great use of space at a time when few retailers considered having third-party restaurant operators in their stores. Most restaurants at retailers were self-branded, like the Zodiac at Neiman Marcus and Lord & Taylor’s Birdcage.

Baker wanted Lord & Taylor to build up its designer assortment, to be more modern and trendier, to balance the store’s traditional, classic, older customer image. But most major designers were far along selling other retailers, so as an alternative strategy he had the business invest in small designer brands, such as Peter Som, Tuleh, Alice Roy, Jeff Mashie and Charles Nolan, and got Joseph Abboud to design Black Brown 1846 for men’s, which was a successful, high-quality men’s private label. The strategy was Baker’s “work around,” meaning his way to attract new designers.

“He thinks abstractly, the way no one did in the fashion industry,” said one former vendor partner.

“Richard brought tremendous enthusiasm, a curiosity that was kind of a breath of fresh air,” said another former colleague. “Most of the leadership in department stores grew up the same way in the business. But Richard came in with an outside perspective. Walking the selling floors, Richard came at it differently. What struck me was that for such an accomplished, wealthy person, he seemed humble, and fun to work with. He is creative. He wanted to do new things. He didn’t know any of the fashion rules.”

However, as Baker got deeper into his retail businesses, “He would be listening less. He felt he had the experience,” the former colleague said.

“There was this arrogance. He didn’t use search firms to hire people,” the vendor said. “He used his network to find people. I’m not sure that he really valued talent.”

He rarely showed up at industry events, didn’t feel the need to be seen, though he did go to the Met Gala a couple of times. While one-on-one he could be personable, he wasn’t one for going out for dinner much. That would have upset his routine of going to sleep early and waking up at 5 a.m. From his estate in Greenwich, where he had a James Turrell-designed indoor pool, he would take his boat down the Hudson River (accompanied by his dog) to his office at Brookfield Place in lower Manhattan.

“He wanted to be the author of a new chapter in luxury retail. He acted like an owner, not as a leader of people so much. In tough times you need that,” the former colleague said.

Baker declined repeated requests for comment.

Richard Baker at a WWD CEO Summit.

Patrick MacLeod