Today, we are going to talk about an aviation story that blends poetry and physics: Concorde’s 1973 solar-eclipse chase. Climbing to 55,000 feet, pushing through the stratosphere at Mach 2, a specially modified Concorde intercepted the Moon’s shadow. It gave scientists aboard 74 continuous minutes of totality — an observational window impossible from the ground. This mission was a vivid demonstration of Concorde’s unique capabilities and remains one of the most emblematic unions of civil aviation and scientific exploration.

In our article, we’ll put that famous flight under the microscope. We’ll also recount the aircraft’s short but glorious history, dig into the technologies that let Concorde do what no airliner had done before, describe the eclipse chase in detail, catalog the records Concorde set, and trace the legacy of those achievements into today’s nascent supersonic renaissance.

From Treaty To Takeoff: Concorde’s Short History

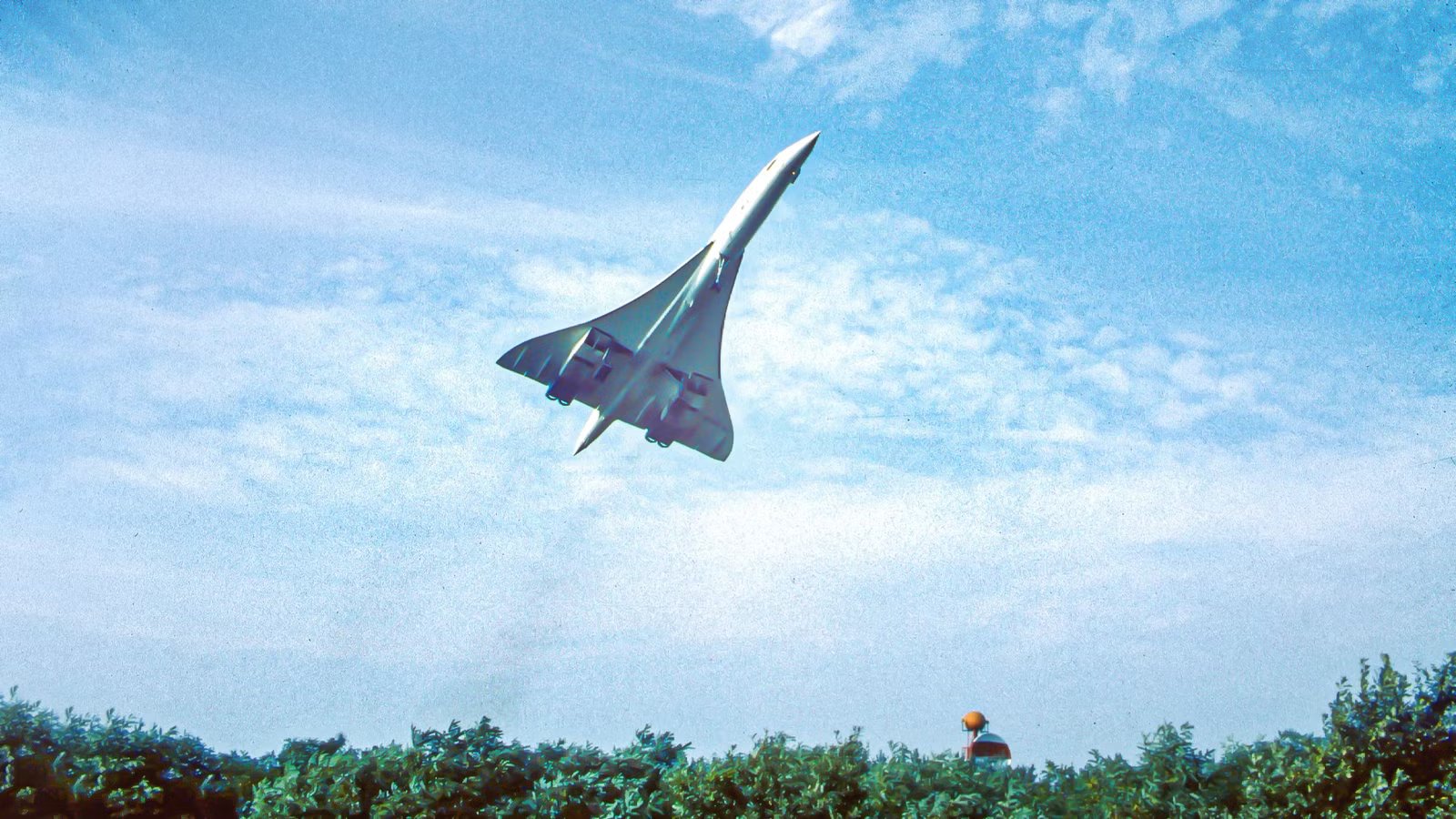

Concorde is a product of the Anglo-French engineering marriage. Born from Cold War-era research into supersonic transport, the project moved from feasibility studies in the 1950s to a 1962 treaty between Britain and France and eventually to the first prototype flights in 1969. The public saw the elegant delta wing in full at airshows and over runways, but behind that graceful silhouette lay decades of aerodynamic theory, metallurgy trials, and political compromises.

Designers adopted the slender-delta wing after research showed it produced stable vortex lift at the high angles of attack Concorde needed at low speeds while remaining efficient at supersonic cruise. The result was an aircraft that could take off and land on conventional runways and cruise at Mach 2.04, carrying about 100 passengers in an era when speed was as much a luxury as legroom. The aircraft’s service life from introduction in 1976 to retirement in 2003 was commercially brief but culturally vast: state visits, celebrity charters, and headline-grabbing records.

Concorde’s program was expensive and politically loaded; only 20 airframes were built, and 14 entered commercial service. Economic realities such as fuel costs, noise restrictions, and limited routes for supersonic overland flight eventually constrained what an otherwise brilliant engineering achievement could do as a business. Yet its technical footprint was enormous: Concorde pioneered practical systems (such as analog fly-by-wire controls and variable engine inlets, as mentioned by the Concorde Heritage website) that influenced later civil and military designs.

What Made Concorde Fast Enough For A Scientific Experiment

Concorde’s ability to intercept a moving shadow and ride within it for more than an hour comes down to three things: power, aerodynamics, and thermal management. The powerplant was the Rolls-Royce/Snecma Olympus 593 — a turbojet with reheat (afterburner) developed specifically for Concorde. The Olympus 593 could provide the takeoff and transonic thrust needed through partial reheat, then cruise at Mach 2 without reheat. This balance of brute force and efficiency was unprecedented for a passenger jet.

Aerodynamically, the delta wing gave Concorde a large surface to generate vortex lift at higher angles of attack, while its ogival shape reduced wave drag in supersonic flow. The variable intake ramps and engine nozzles were computer-controlled to manage shock formation and ram pressure recovery — essential plumbing that let the engines breathe cleanly at Mach 2. Add the droop-nose (for cockpit visibility on approach), and you see how the design married practical airport operations with extreme cruise conditions.

Thermally, kinetic heating was a constant design factor. At Mach 2, the airframe skin warmed noticeably. Engineers chose durable alloys and designed them for cyclic heating and cooling; panels and windows would be warm to the touch after cruise. These metallurgical choices actually capped Concorde’s top sustainable speed (the highest structural temperatures the aluminum alloy could safely tolerate set practical limits around Mach 2.02). Much of Concorde’s everyday operating envelope, therefore, represented a negotiated balance between speed and material longevity.

Why Did Blue Paint Cause Issues For Concorde?

One simple color change pushes the Concorde to its limits.

The 1973 Eclipse Chase: Planning, Execution, And Results

The Concorde solar eclipse mission of 30 June 1973 looks like a flight plan worth publishing in an astronomy textbook. The prototype, Concorde 001 (F-WTSS), departed Las Palmas, Canary Islands, at 10:08 GMT and climbed to its working altitude. Scientists and engineers had fitted the prototype with observation ports and instruments to study the corona and chromosphere during totality. The idea was elegant: the Moon’s shadow races across Earth at thousands of kilometers per hour; a Mach-2 aircraft could match that speed and ride inside the umbra far longer than any land observer, as described by The Aviationist.

Flight planning for such an interception was a nice mathematical exercise. The team computed the ground track of the umbra, wind, and jet stream effects, and the aircraft’s fuel and mass state at cruise altitude. Concorde’s speed profile, accelerating to and holding around Mach 2 while maintaining a 55,000-ft flight level, aligned with the shadow’s motion over West Africa. Onboard telescopes and instruments were pointed through specially installed portholes for a continuous, 74-minute totality — a record for eclipse observation and, to this day, the longest duration captured from an aircraft.

1973 Eclipse Flight Facts

|

Category |

Details |

|

Mission Date |

30 June 1973 |

|

Aircraft Used |

Concorde 001 (registration F-WTSS) |

|

Departure Airport & Time |

Las Palmas Airport, Canary Islands (10:08 GMT) |

|

Cruise Altitude |

Approximately 55,000 ft |

|

Cruise Speed |

Around Mach 2 (≈1,350 mph / 2,170 km/h) |

|

Eclipse Observation Duration |

74 minutes of continuous totality (airborne record) |

|

Flight Objective |

To intercept and remain within the Moon’s umbral shadow |

|

Scientific Equipment Onboard |

Five dedicated experiments |

|

Research Focus Areas |

Solar corona, chromosphere, and infrared radiation |

|

Historical Significance |

The most extended solar eclipse observation ever achieved from an aircraft |

Scientifically, the flight offered a cleaner line of sight than ground stations, with less atmospheric scattering and turbulence, enabling more precise infrared and coronal measurements with less noise. Five experiments are recorded from the mission, though later literature notes their impact was modest compared with the publicity value and proof-of-concept that a high-speed platform could dramatically extend transient astronomical observations. The mission’s success owed as much to Concorde’s flight characteristics as to the meticulous collaboration between pilots, scientists, and engineers.

Other Concorde Records And Milestones

Concorde was a record-breaker and an attention magnet across multiple dimensions. In 1996, ![]() British Airways flew a scheduled Concorde from New York JFK to London Heathrow in 2 hours, 52 minutes, and 59 seconds — a passenger transatlantic speed record often cited in museum placards and press retrospectives. Meanwhile, military platforms hold a different class of speed trophies: the SR-71 broke transatlantic and coast-to-coast speed marks that remain unmatched, but those were reconnaissance missions, not civilian scheduled services. Concorde’s records sit in the crowded space where public spectacle, passenger convenience, and pure aeronautical performance intersect.

British Airways flew a scheduled Concorde from New York JFK to London Heathrow in 2 hours, 52 minutes, and 59 seconds — a passenger transatlantic speed record often cited in museum placards and press retrospectives. Meanwhile, military platforms hold a different class of speed trophies: the SR-71 broke transatlantic and coast-to-coast speed marks that remain unmatched, but those were reconnaissance missions, not civilian scheduled services. Concorde’s records sit in the crowded space where public spectacle, passenger convenience, and pure aeronautical performance intersect.

Beyond the famous transatlantic dash, Concorde achieved other technical “firsts”: a commercial aircraft that routinely cruised at Mach 2, pioneering variable-intake control and supercruise capability for a passenger jet, and practical solutions for supersonic structural heating and fatigue. Some of these achievements are footnotes in textbooks; others, like flyovers for state occasions and the spectacle of the droop-nose, entered popular imagination. Concorde 001 itself accumulated 812 flight hours, including 255 supersonic hours, during its flight-test life before being retired for museum display — a factual marker of prototype testing intensity. You can find out more about this magnificent aircraft and see it on display at Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace (Le Bourget Aviation Museum) in Paris.

Concorde Records & Milestones

|

Category |

Notable Record / Fact |

|

Longest airborne eclipse observation |

74 minutes (30 June 1973) — Concorde 001. |

|

Fastest passenger transatlantic flight |

2h 52m 59s (BA Concorde). |

|

Prototype test hours (001) |

812 hours, 255 supersonic. |

|

Engine efficiency (Olympus 593) |

~43% in supersonic cruise — very high for thermodynamic machines of the time. |

Concorde also left a mark on cultural currency: it was a symbol of status and national pride, used by heads of state and celebrities. It later became a design icon in both Britain and France. The 1973 eclipse mission added a unique scientific record of the most extended continuous eclipse observation from an airborne platform, a feat no commercial airliner has replicated at that scale and one that remains a proud oddity in Concorde’s ledger.

What Was The Longest Concorde Flight?

It only took four hours and ten minutes for the supersonic airliner to cross the pond.

The Human Side: Crew, Scientists, And The Passenger Experience

It’s easy and fascinating to talk about numbers related to Concorde, such as Mach, feet, and minutes. But the success of the eclipse chase owed as much to human craft as to metal and thrust. Pilots tasked with flying the exact shadow-matching track relied on precise navigation, calm decision-making, and intimate knowledge of Concorde’s performance envelope. Scientists had to adapt instruments to the vibrations, thermal environment, and limited observation geometry of an aircraft platform. Cabin crew and mission staff recreated a functioning laboratory in a narrow fuselage, where every kilogram of extra kit affected fuel burn and range. It was a challenging task, but worth every penny.

Passengers on Concorde lived a peculiar duality: inside, a quiet, pressurized, luxurious cabin; outside, a roaring, kinetic spectacle at twice the speed of sound. For those aboard in 1973, the eclipse was an extended encounter with a cosmic event — a phenomenon framed by a near black sky and the curvature of Earth. The mission blurred the line between commercial travel and airborne research, showing how an airliner could be temporarily repurposed into a scientific observatory with meaningful returns.

Legacy And The Road Ahead

Concorde was retired in 2003 for a tangle of economic and safety reasons: a fatal crash in 2000, rising maintenance costs for an aging fleet, and an air travel market reshaped by fuel prices and demand. But the technical and cultural legacy is durable. Concorde proved supercruise, practical variable intakes, and solutions to thermal cycling — all of which feed into modern designs. Museums preserve airframes (including Concorde 001 at the Le Bourget Aviation Museum in France and others across museums in the UK, Germany, and the USA).

The present supersonic renaissance, such as startups building new SST concepts, demonstrator prototypes quietly testing sonic regimes, owes part of its social license to Concorde’s legendary status. Modern programs aim to be more efficient, quieter, and economically viable than their ancestor, addressing the exact limitations that grounded Concorde. But most importantly, the romantic image remains: a sleek jet chasing a shadow across a sunlit continent, crossing it faster than a bullet. That image keeps Concorde alive in the collective imagination and provides a yardstick for what human ingenuity can still achieve.

Additionally, Concorde’s eclipse chase was not a PR stunt the aircraft was famous for. This flight was a practical demonstration of how speed, altitude, and planning can transform scientific opportunities. As new engineers and entrepreneurs imagine the next generation of fast flight, Concorde’s textbook of solutions and its flights of historical and scientific importance, such as the 1973 eclipse, will remain essential reading.