Forthcoming legal proceedings against Meta and YouTube are frequently referred to as the “social media addiction trials”, but whether these platforms are truly addictive is still the subject of scientific debate.

The lawsuits were brought against Meta, YouTube (Google), Snap Inc and TikTok by plaintiffs alleging these platforms severely damaged their mental health when they were children. Snap and TikTok settled the first case to go to trial, brought by a woman known as KGM, now about 20. The remaining defendants, Meta and YouTube, were set to go to court this week, but the trial was delayed because Meta’s senior attorney became ill.

Notably, the plaintiffs’ cases do not hinge exclusively on the idea that they became addicted to the platforms. They allege addiction as the precursor to other severe harms, including depression, eating disorders, self-harm in the form of cutting, attempted suicide and, in at least one case, death by suicide.

The firms pushed back strongly on the claims. “Providing young people with a safer, healthier experience has always been core to our work … The allegations in these complaints are simply not true,” a Google spokesperson said.

“We strongly disagree with these allegations and are confident the evidence will show our longstanding commitment to supporting young people,” a Meta spokesperson said.

TikTok and Snap Inc did not respond to a request for comment.

Experts say proving, scientifically, that social media is addictive would be difficult, especially as the research community on the issue is moving away from the term “addiction” and more towards terms like “problematic use” or “use disorders”.

Ofir Turel, a professor of information systems management at the University of Melbourne, and Dr Jessica Schleider, a clinical psychologist at Northwestern University, both acknowledged that social media can be harmful, but resisted calling it “addictive”.

Turel said the term has become too common. “Everybody is saying, ‘I’m addicted,’ like it’s not a medical term. And this is where things become murky,” he said.

“This is an incredibly complicated and also hot-button issue among scientists,” Schleider said.

Lawsuits against the platforms allege that they borrow “heavily from the behavioral and neurobiological techniques used by slot machines and exploited by the cigarette industry.”

While Schleider acknowledged that core features of the platforms, such as social comparison metrics, endless scroll and algorithmic amplification of polarizing topics, are all “built to keep people there. They’re not neutral. They shape attention, emotion and behavior,” she said that this does not necessarily make them addictive.

“There’s a preponderance of evidence at this point on the association between social media use and mental health outcomes, including addiction,” Schleider said, but added that results are mixed and the average negative impact of social media is small across large, well-conducted studies. The relationship between social media and mental health is complex and possibly “bidirectional”, meaning that poor mental health might drive social media use in addition to social media use driving poor mental health. So it’s important not to simply conclude that social media is “the singular driver of the youth mental health crisis”.

While Schleider emphasised that large-scale research finds social media has only a small negative mental health impact at the population level, Schleider also said individual harms might be more severe, and that plaintiffs could prove that the platforms harmed them.

Meta allegedly attempted to bury research it conducted in collaboration with Nielsen that found temporarily pausing Facebook ameliorated participants’ feelings of depression, loneliness and anxiety.

A spokesperson for Meta said the research was discontinued because the participants’ improved symptoms were due to the placebo effect.

The American Psychological Association also derided Zuckerberg for cherrypicking from one of Meta’s reports to claim no link between social media and negative mental health outcomes, when the report in fact named multiple risks.

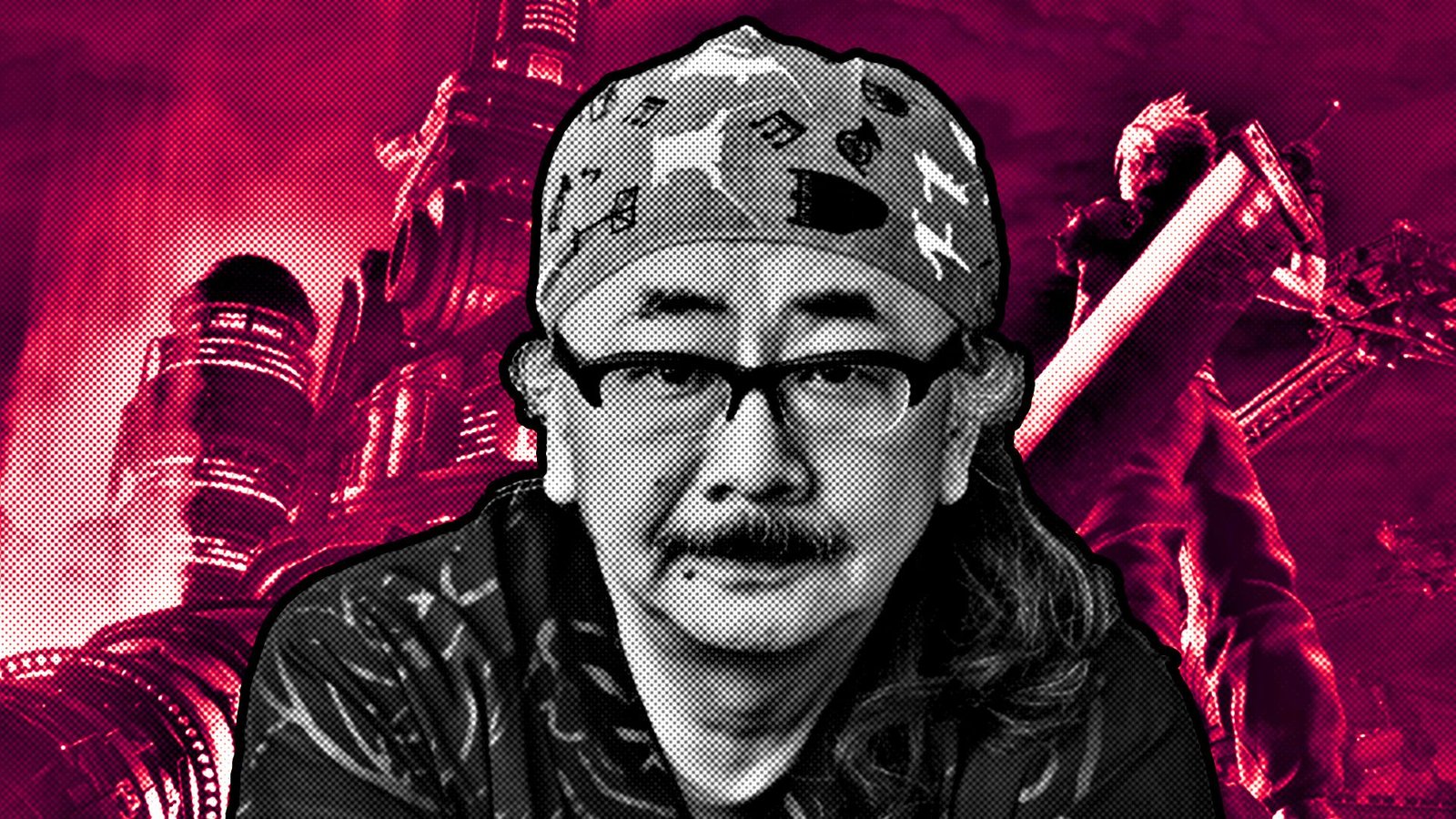

Turel has conducted brain-imaging research showing that excessive social media use is associated with differences in the brain similar to excessive gambling. Gambling disorder is the only behavioral disorder – as opposed to substance-use disorder – in the chapter of the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) on addiction. Social media companies have been known to exploit the same “intermittent reinforcement”, mechanism that makes gambling so compelling.

There are “different flavors of addiction”, Turel said, and the distinctions are important. Addiction affects both the “reward system”, primarily governed by dopamine release, and the “self-control system”, primarily governed by the prefrontal cortex, according to Turel. He compared the “reward system” to the accelerator in a car, and the “self-control system” to the brakes. When addicted, people jump on the accelerator without thinking, and their ability to step on the brakes might also be impaired.

In some substance-use disorders, like cocaine-use disorder, long-term use can permanently damage both parts of the brain, Turel said. But so far as we know, behavioral disorders just don’t cause this type of irreversible damage. While they might temporarily affect the “accelerator” in the brain, they don’t affect the “brakes”, and that change is reversible over time.

Turel also said withdrawal symptoms in substance addictions are much more intense. “Let’s say you don’t have access to social media. What are the symptoms that you’re going to feel? You’re going to be agitated for a while, and that’s it,” Turel says. Whereas substance withdrawal can cause nausea, excessive vomiting, severe migraines and chills.

Simply being unable to stop a behavior is not enough for the DSM to define it as an addiction. People must be unable to stop despite negative consequences. This, too, looks very different between social media and established substance addictions. The risks of jail time, psychosis or overdose are severe compared with the typical compulsive social media users’ risks, like less engagement with hobbies and friends.

While the plaintiffs’ cases connected social media “addiction” to other extreme harms including suicidality, the causal link is harder to establish than, say, the link between methamphetamine overuse and psychosis, or opioid use and depressed breathing leading to overdose.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends the term “problematic use” when it comes to social media for these reasons, and also because social media provides benefits like information sharing and connection as well as harms.

Despite the hesitation to use the addiction label, many scientific academies and organizations still acknowledge that social media can be harmful, especially to minors, whose brains are still developing. Many of them call for increased regulation and consequences for the platforms.

When smokers and their loved ones first began suing tobacco companies, there wasn’t yet scientific consensus on tobacco’s harms, either, though these companies also attempted to influence evidence in their favor.

Turel sees this as a similar moment. We now know that cigarettes cause not only addiction but many kinds of cancer as well as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

“Social media is much more than an addictive machine. It has many other issues, with fake news, with cyberbullying and body image. And we are becoming aware of them and trying to control them.”