Jesse Jackson was a “direct connection to the great era of civil rights”, Diane Abbott said, leading UK tributes to the African American campaigner.

The Rev Jackson was also intimately connected to the battle for racial equality in the UK, where he campaigned for decades to address institutional racism, as well as economic, health and criminal justice inequalities.

“His message is absolutely relevant today, when we are seeing a resurgence of racism in a way that we hoped had been banished,” Bell Ribeiro-Addy, the MP for Clapham and Brixton Hill and chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Afrikan Reparations, said in tribute to the civil rights leader, whose death, at the age of 84 was announced on Tuesday.

She added: “He stood on a (pan-African) tradition that we saw from the likes of (Marcus) Garvey and (Kwame) Nkrumah, that international solidarity was key to the liberation of peoples of African descent.”

That lifelong journey of solidarity brought Jackson to Manchester, to a packed Church of God of Prophecy in Moss Side in 2007.

That visit marked the 200th anniversary of the abolition of slavery – the industry that had fuelled the city’s wealth, while scarring the ancestors of so many of its Black residents.

Jackson’s visit to Manchester – part of a nine-city “Equanomics” tour that also stopped in Birmingham, Bradford, Bristol, Leicester, Liverpool, London, Nottingham and Sheffield – reflected how, for Jackson, economic, racial and social justice were inseparable, and how African descendant communities in the UK and America were linked by the shared experience of Black minority status in the west.

To rapturous applause from Black communities across the country, Jackson prefigured the conversations that became mainstream in the UK – after the death of George Floyd in the US – about the UK’s failure to recognise the Black contribution to the national story.

In Bristol, Jackson told his audience: “We as Africans are creditors, not debtors. Our energies fuelled the Industrial Revolution. We fought and died in World War One and World War Two.

“In Bristol, you are the creditors. You are owed. Have a new sense of yourselves. You are the creditor, not the debtor. Today we are free but not equal.”

Throughout his life, whenever Black British communities reeled – in the aftermath of uprisings, killings and systemic injustices – Jackson was an encouraging, inspirational presence, flying over from the US to stand with affected communities. He was there for landmark moments, too, meeting Diane Abbott, the country’s first Black female MP, who remembers him as “very smart, warm and hugely charismatic,”.

Two years before Abbott’s election, Jackson had urged Margaret Thatcher to drop UK support for apartheid in South Africa, after joining with Abbott, Paul Boateng, Bernie Grant and Ken Livingstone at a Trafalgar Square protest to end apartheid and free Nelson Mandela attended by 120,000 people.

He had long fought against the marginalisation of Black history. When the pan-African activist Akyaaba Addai-Sebo, then a worker at the Greater London Council, staged the lectures and concerts that would sow the seeds for UK Black History Month, Jackson was among the attenders – alongside activists Angela Davis, Winnie Mandela, Marcus Garvey Jr and musical greats Ray Charles, Burning Spear, Hugh Masekela and Max Roach.

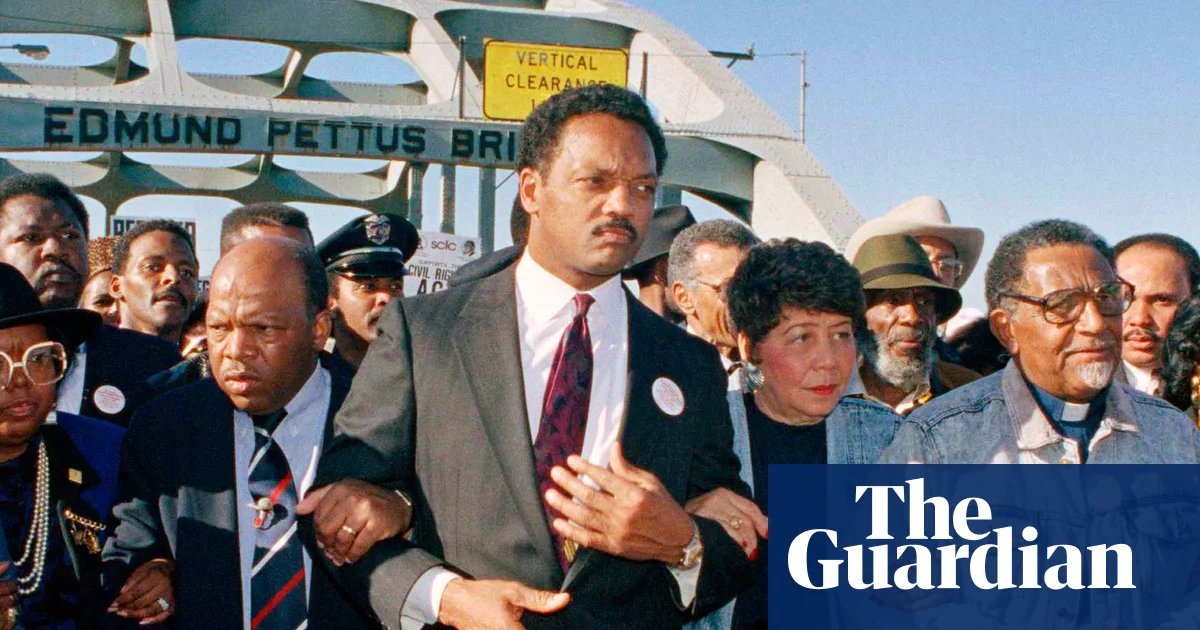

Having grown up in the segregated American South, campaigning for civil rights and economic justice alongside Dr Martin Luther King, Jackson was a lifelong campaigner for democratic participation.

In 2013, 50 years after King was assassinated, Jackson came to the UK in support of Operation Black Vote, a cause he backed for years, and spoke of how he hoped the US civil rights struggle would continue to inspire campaigning for unity and equality in the UK.

He told the BBC: “When we got the right to vote in 1965, it was not just Blacks as was commonly thought; white women couldn’t serve on juries, 18-year-olds couldn’t vote, you couldn’t vote on campuses and you could not vote bilingually, so we had to learn to move from surviving separately to living together.

“Inclusion leads to growth, when there’s growth everybody wins … When you look at whoever’s playing football in this country, why do they do so well in football, Black, white together? Because when the playing field is even and the rules are public and the goals are clear, the referee is fair and the score is transparent, we do well.”

After news broke of Jackson’s death, Operation Black Vote founder Lord Simon Woolley told the Voice: “I was fortunate enough to know him not only as a public figure, but as a mentor and collaborator. Together, we worked to register tens of thousands of Black and Brown voters here in the UK. What began as inspiration grew into a friendship that lasted nearly 30 years.”

Ribeiro-Addy recalls having to be told gently by Woolley to wrap up a speech she gave at an event where Jackson appeared in Nottingham, more than 15 years ago, which was running over time as she “really wanted to impress” him.

She added: “I went on to work for Diane Abbott and met him a good few more times – whenever we had elections in the UK, he would come over. He got the importance of it. He stood on the shoulders of those who came before and continued to show us that the international solidarity that we had to share as Black people knew no borders.

“He had the inspirational audacity to run for president. He showed us that while we are fewer in number in the UK, we could achieve something – and we did in terms of political representation, which he fought for in the UK by coming over and empowering people and showing them that if they could do it there, we could do it here.

“We saw those first four Black MPs being elected in 1987 – and I now sit as a member of parliament in the most diverse parliament this country’s ever seen.”