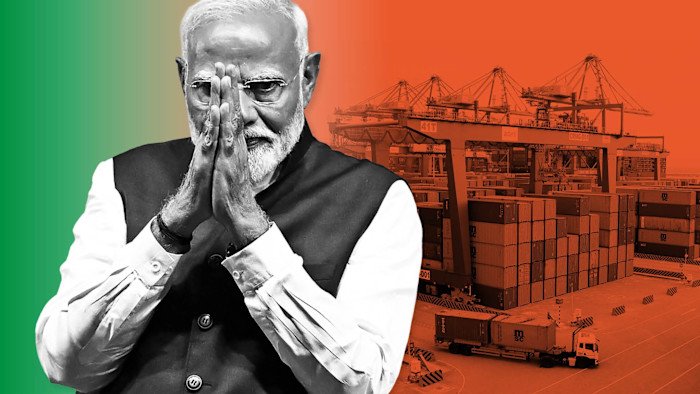

Indian parliamentarians thumped their desks and shouted Narendra Modi’s name last week as the Indian prime minister heralded a new trade pact with the US, only a week after agreeing a full-blown trade agreement with the EU.

“A self-confident India has today emerged as a trusted partner of many countries around the world,” Modi declared. “The trade deals concluded with the European Union and America are vivid examples of this.”

Analysts said the Modi government’s move to cut tariff-busting deals with Europe and the US marked a historic shift in tack for one of the world’s most protectionist economies, which has zealously guarded domestic markets since its founding in 1947.

“These deals will leave India with tariff rates on manufactured goods that could never have been dreamt of just two or three years ago,” said Arvind Subramanian, a former chief economic adviser to Modi now at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

As details of the US-India pact emerged over the weekend, opposition voices accused Modi of “surrendering” to Trump on agricultural tariffs and a pledge to stop buying Russian oil, but commerce minister Piyush Goyal said that the agreement would “open a $30tn market for Indian exporters”.

The US deal spoke to twin realities confronting the Modi government at home and abroad. India now finds itself squeezed between a volatile US and an adversarial China, while at the same time needing to turbocharge labour intensive manufacturing to create more of the kind of export led growth seen in other Asian countries.

Modi has pursued an active trade agenda since taking office in 2014, but Trump’s decision to jack up tariffs on India’s exports to 50 per cent to penalise New Delhi for continuing to buy Russian oil spurred him to pursue wider-ranging agreements over the past year, analysts said.

The deals with the world’s two largest consumer markets follow smaller agreements with the United Arab Emirates and Australia in 2022, the European Free Trade Association in 2024, and the UK and New Zealand last year.

The comprehensive EU agreement, which is the most far-reaching ever signed by India, and the US pact will accelerate the integration of India into the global trading economy.

India will still protect its big and politically sensitive foodgrain and dairy markets in both the EU and US pacts, but allow freer access than before for imported foodstuffs that it relies on such as apples and pulses.

India has also agreed to remove or reduce high duties on EU industrial products including chemicals, cosmetics and cars, which currently average above 16 per cent, although some reductions will be phased in over 10 years. Its tariffs on EU cars will be gradually reduced from 110 per cent to 10 per cent, with a quota of 250,000 vehicles a year.

Analysts said the need to alleviate pain from Trump’s tariff hikes, which were hitting key exports including clothing, gems, jewellery and fish, helped seal an EU-India agreement that had been nearly 20 years in the making.

The deal with Brussels, in turn, prodded Washington to break its impasse with New Delhi, analysts said.

“India’s emerging basket of non-US trade agreements . . . were beginning to cause disquiet among individual US business and export constituencies,” said Ashok Malik, head of India practice with The Asia Group, a US-based strategic advisory firm. “I guess someone in Washington, DC finally did the math.”

Driving the shift in India is Modi’s push for a new growth model in which exports from its long underperforming manufacturing sector play a much greater role in its traditionally insular economy.

India is also hoping to trigger a surge of investment in manufacturing at a time when net foreign direct inflows are at three-year lows, according to Financial Times’ fDi Markets data.

For Modi, a leader with one eye on his place in history, success would place him among India’s most consequential reformers since then-prime minister PV Narasimha Rao opened the economy to foreign investment in 1991.

Modi has pledged to make the country a developed economy by 2047, a target analysts warn will be tough to achieve.

“The stakes are very high as other growth strategies have not worked,” Subramanian said. “India’s current share of global trade in labour-intensive manufactured goods is less than 2 per cent, if it could get to 10 per cent, even, that would be a significant step forward.”

India’s manufacturing base was given a boost last year by Trump’s return to the White House, when high US tariffs on goods from China drove Apple to switch more of its iPhone manufacturing to factories run by Foxconn and Tata Electronics in southern India.

Cumulative iPhone exports from India exceeded $50bn in December — up from zero in early 2022 — a standout success in India’s belated bid to become a “factory Asia” manufacturing power.

In one of the biggest immediate wins for New Delhi, EU levies on Indian textiles — one of the sectors hardest hit by the US tariff regime — are scheduled to fall from more than 10 per cent to zero. The industry hopes a deal with Washington will follow suit and is calling on India’s government to remove import duties on cotton to reduce input prices as part of an ambitious plan to triple Indian textile exports from $37.5bn to $100bn a year by 2030.

Ashwin Chandran, chair of the Confederation of Indian Textile Industry, said a US deal was a “highly positive development” for the labour-intensive sector that is an important provider of jobs. “Reducing tariffs will ensure our textile and apparel exporters are once again in a position to compete effectively in the US market,” he said.

Liberalisation will not happen overnight, however. As well as phasing in tariff cuts over more than a decade, India is ringfencing its sensitive wheat, rice and dairy sectors, which employ tens of millions of people.

Some analysts also doubt whether Modi’s government, which has introduced moderate supply-side reforms to soften labour rules and unionisation, has the ability to transform the share of India’s GDP generated by trade.

The initial opposition to the US pact also demonstrates that trade liberalisation remains fraught with political difficulty for any Indian government.

“Modi is the most powerful prime minister since Indira Gandhi, but so far reforms have been incremental,” said Pratik Dattani, founder of the Bridge India think-tank. “India needs to make once-in-a-generation reforms to deliver a step change, and it’s hard to see that happening.”

And despite India’s embrace of bilateral dealmaking, diplomats at the World Trade Organization in Geneva say they do not expect India — long a blocker of WTO reform — to radically alter its approach.

“India distinguishes very strongly between deals it does bilaterally and the multilateral sphere. Its general disposition in the WTO is obstructionist, and everyone expects it to remain so,” said one WTO ambassador.

Additional reporting by Jyotsna Singh in New Delhi