Part one recap: John Rosenthal, accountant to the wealthy, was also their best friend. Wanting to play in the big leagues where his clients lived, Rosenthal began an investment scheme, promising big returns. The clients placed their trust in him, giving over millions on little more than a handshake.

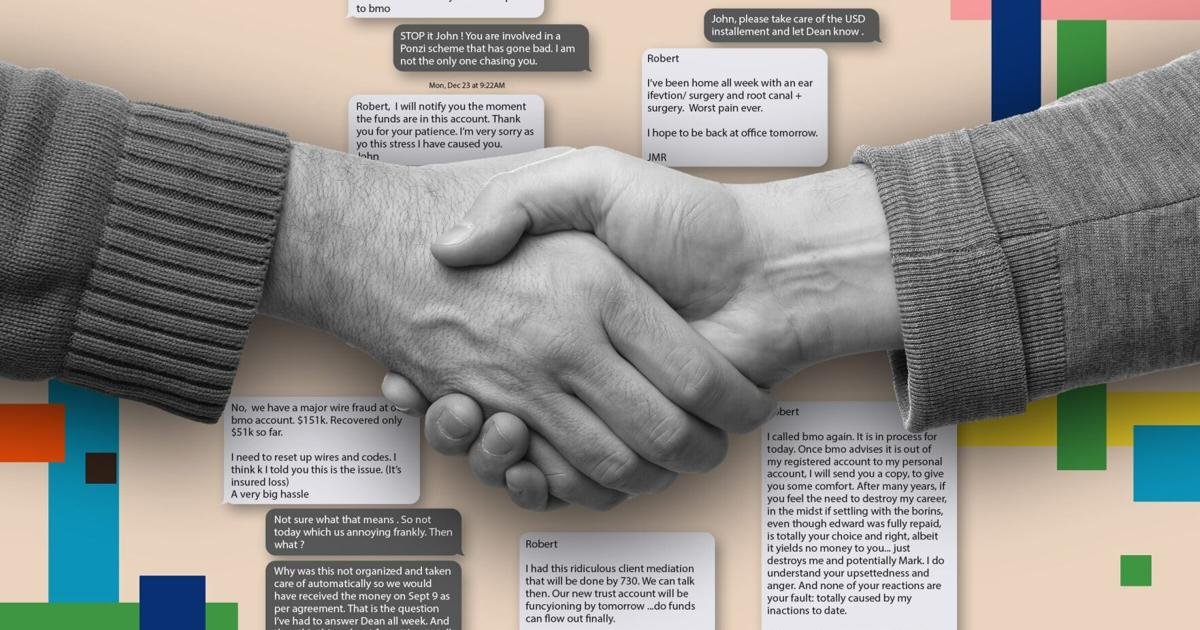

“I am sick like a dog,” John Rosenthal texted his client, investor and friend, Robert Sidi, in September 2024. A monthly interest payment cheque from Rosenthal had bounced, and Sidi had asked what the problem was. Rosenthal said he’d deal with it as soon as he was back on his feet.

Sidi felt badly for his friend. He waited a few days, and politely asked again. There was a new issue, Rosenthal told him.

“Major wire fraud,” Rosenthal texted. His bank accounts were frozen. “Last week was a disaster.”

John Rosenthal texts with Robert Sidi over the sickness excuse.

Court file

Sidi and one of his companies had invested a total of $320,000 earlier in 2024 in a real estate “investment opportunity” that Rosenthal had pitched, promising a return of 9.8 per cent. “Thanks for your patience,” Rosenthal texted when monthly cheques bounced. He promised the cheque was in the mail. Today, Sidi has alleged in court filings that he is out $156,000.

By the fall of 2024, other investors were hearing from Rosenthal and his partner, Mark Zaretsky, that they could not make a monthly payment. Zaretsky told one investor their firm had been hit by a “cyber attack.” Rosenthal told another he’d goofed, “erroneously” failing to set up the payment. A woman who had invested $235,000 from the sale of her house after her husband died was told by Rosenthal that a “fraud” at the bank was the cause of the delay.

Toronto lawyer Peter Israel, one of Rosenthal’s closest friends, was mystified when monthly interest cheques from $300,000 investments he and his wife had made bounced. He was sure there was a good explanation. He and Rosenthal regularly vacationed together; he and his wife often had Rosenthal over to their house. After all, Rosenthal had done accounting work for him for two decades and there had never been an issue.

Israel tried to get him on the phone. Then he sent a worried email asking what was going on, and if his money was safe.

“I have had nothing but love and respect for you for more than 20 years,” Israel told him. “I care for you.”

Rosenthal responded that he would be “resolving our issues shortly.”

That never happened. Israel and his wife, also a lawyer, had advanced Rosenthal hundreds of thousands of dollars to fund what they were told were real estate investments — loans he believed were funding building projects. Long after he should have, Israel turned his “lawyer’s mind” on and realized that the money they had “invested” was lost.

“John,” Israel wrote, “I am getting concerned that these loans don’t exist as indicated.”

Star Investigation: Part 1

John Rosenthal, whose tax advice was always highly sought after, faces millions in claims in 15 court actions. He says he’s broke. First of two parts.

Star Investigation: Part 1

John Rosenthal, whose tax advice was always highly sought after, faces millions in claims in 15 court actions. He says he’s broke. First of two parts.

Across Toronto in the fall of 2024 and into the winter, dozens of people noticed their interest cheques from Rosenthal were bouncing. Some held out hope. Others believed their money was gone, and hired a lawyer to sue the 75-year-old Rosenthal.

Sidi, who had owned and operated several successful Toronto businesses, believed he was the victim of a financial scam.

“By December 17, 2024, I suspected that (Rosenthal’s partner Mark Zaretsky) and John Rosenthal had involved me in a Ponzi scheme and Rosenthal’s excuses for non-payment were dishonest,” Sidi says in an affidavit filed with the Superior Court of Justice, one of a dozen lawsuits currently in play against Rosenthal and Zaretsky.

“I was extremely upset that Rosenthal had abused my trust as a friend and as my accountant,” Sidi wrote.

The phrase “Ponzi scheme” hearkens back to Carlo Ponzi and a century-old fraud in Boston. A “Ponzi” is an investment scheme that promises high rates of return with little risk to investors. In a true Ponzi scheme, there is no real investment — no real estate or other security. But it only works as long as new investors keep coming in. New investor money is used to pay the earlier investors, and so on. When new investors dry up, the scheme unravels. Five years ago, the Star profiled a Ponzi scheme run by a (now deceased) OPP officer, who promised interest rates over 20 per cent.

Allegations that Rosenthal and Zaretsky were running a Ponzi scheme have not been tested in court. Investors alleged to the Star that they believe this is what was happening. Sidi, in his pleadings in court, alleges the men were operating such a scheme. Neither Rosenthal nor Zaretsky has responded to, or filed a defence in, any of the lawsuits filed against them.

John Rosenthal giving a speech. There are 15 lawsuits against him filed in Superior Court in Ontario, with claims totalling more than $13 million, but sources close to the case say many people did not sue, thinking there was no money.

Supplied

Some new investors question whether they could somehow have been warned — some put money in when the scheme was unravelling.

The Star’s investigation reveals that while it was late 2024 when many investors ran into trouble, some saw problems earlier, including well-known Toronto bookseller Edward Borins, whose chain of bookstores (Edwards Books and Art) was a staple on Queen Street West and other locations for many years.

Borins had used Rosenthal and his partner Zaretsky as accountants for many years, and Borins and Rosenthal became close friends. Starting in 2012, Rosenthal added an entrepreneurial side to their business. He told his best clients he was fronting some real estate deals. If they wanted to make a strong return, they should buy in.

An early investor was Dianne Firth, a widow, who had sold her home and invested the proceeds ($235,000) with Rosenthal. She trusted him — he was a family friend and was the godfather to her daughter. Firth would eventually sue Rosenthal, but not until the interest cheques bounced in 2024.

But Borins ran into trouble with Rosenthal much earlier. Between 2014 and 2017, Borins invested $815,305 with Rosenthal and Zaretsky.

All went well at the start. But in 2018, a financial adviser working for Borins started questioning the lack of documentation around the investments. Facing pressure by Borins, Rosenthal returned some of the money, but none of a $500,000 investment, which was the largest and most recent of six investments. Borins sued. And he made a complaint in the summer of 2021 to the Chartered Professional Accounts of Ontario, which regulates accountants.

Complaints made against an accountant are only made public if a charge is laid by the regulator. In Rosenthal’s case, the CPA Ontario investigation continued for two years, and most of Rosenthal’s investors were completely unaware.

Facing an investigation by the regulator, Rosenthal and Borins discussed a settlement.

In 2023, when Rosenthal was about to settle with Borins — paying the $500,000 back — Rosenthal added a caveat. Borins was to write a letter to the regulator. According to the regulator’s written reasons for stripping Rosenthal of his accounting licence, Rosenthal’s lawyer drafted the letter for Borins to sign:

“I write to confirm that the loan at issue in my complaints has now been repaid. As a result, I no longer wish to pursue my complaints against (Rosenthal and Zaretsky),” the letter states, adding that Borins (who did not sign the letter) no longer felt the accountants had done anything wrong.

Borins contacted the regulator and was told that a complaint could not be withdrawn. By the summer of 2023, Rosenthal paid the $500,000 back to Borins. Later that year, the Chartered Professional Accountants of Ontario regulators filed charges against Rosenthal and Zaretsky, alleging professional misconduct. Among the specifics, that they “comingled” investor funds in their general accounts; used investors’ funds to make loans to “third parties”; and that they withdrew investors’ funds “without the investors’ knowledge or approval.”

Another allegation levelled against Rosenthal is that he required Borins to withdraw his complaint as a “pre-condition” for Borins to be repaid. Some later investors wonder if it was their money that paid Borins back.

The CPA Ontario investigation did not become public until September 2023, when it laid regulatory charges against Rosenthal and Zaretsky. The charges were on the regulator’s website, but no media picked up on the case.

A public hearing was not held until 2024. Few knew about pending charges, and so investors continued to pour money in Rosenthal’s direction, according to lawsuits against Rosenthal and Zaretsky.

Michael Levine, a Toronto businessman who had also invested with Rosenthal, and considered him his “best friend,” stood by Rosenthal at the regulatory hearing.

“With the Ed Borins thing, I held his hand through the entire thing,” said Levine. Eventually, Levine, too, would be out money.

The exact total dollar value invested, owed, and the number of investors is unknown. There are 15 lawsuits filed in Superior Court in Ontario, with claims totalling more than $13 million, but sources close to the case say many people did not sue, thinking that, as one investor said, “you can’t get blood out of a stone.”

At the hearing in 2025 on Borins’s complaint, Rosenthal showed up; Zaretsky did not.

The hearing panel concluded that Rosenthal and Zaretsky had committed “professional misconduct.” Both were stripped of their licences. Rosenthal was fined $75,000 and banned from reapplying for his licence for five years. Zaretsky was fined $50,000 and given the same restriction on reapplying.

In its judgment, the regulatory panel found that Rosenthal “converted” Borins’s investment funds “for his own use.” That he ultimately repaid Borins did not help his case, the panel said, noting that he had tried to get Borins to withdraw his complaint, which the panel said was “self-serving, corrupt, and potentially harmful to the administration of justice.”

“Rosenthal exploited (Borins’s) misplaced trust in his professionalism and friendship and took advantage of that trust to use (Borins’s) funds for his own benefit,” the panel ruled.

Rosenthal declined the opportunity to present “mitigating facts,” the panel ruled, and it heard no “evidence of remorse, insight or rehabilitation.”

When it came to Zaretsky, the panel found that he played a lesser role in the scheme, but noted he followed “Rosenthal’s lead” and failed to stop him from using Borins’s money for Rosenthal’s “partnership withdrawals.”

Two other prosecutions by the Chartered Professional Accountants of Ontario based on complaints by other investors, and the regulator’s allegation that neither man co-operated with its probes, resulted in duplicate orders last fall stripping them of their licences. Rosenthal received an additional fine of $115,000, Zaretsky $65,000. Their firm RZN, LLP was deregistered, meaning it can no longer practise accountancy. The firm has been fined a total of $65,000 from two of the cases.

The fines have not been paid. However, if either man wants to be an accountant in Ontario again, he would have to pay the fines.

The Star has tried to reach both men for the past three months. Zaretsky was eventually reached by a Star reporter at the front door of his Toronto home. He said he had moved on with his life and did not want to discuss the cases against him.

Mark Zaretsky, John Rosenthal’s former partner, has also been stripped of his accountant licence in Ontario. Zaretsky has declared bankruptcy.

Facebook

He declared bankruptcy last September, owing $17.9 million. Many of the claims against him are from investors ($13 million of the total amount), who have made similar claims against both Rosenthal and Zaretsky in court. Creditors who have registered the amount they are owed on the bankruptcy documents include wealthy investors, and people who have lost life savings. Bradley Vooren, who with a former business partner is out $250,000, recalls a heartbreaking moment during a telephone call involving numerous creditors.

“There was an elderly lady who invested her life savings and broke down crying on the call,” Vooren said. “It was not all wealthy, sophisticated investors impacted by this fraud and I find it truly perplexing that police have not stepped in or launched a formal investigation to date.”

One claim against Zaretsky on the bankruptcy statement is from Marcia Lipson, Rosenthal’s wife, who appears to have advanced $1.9 million to the scheme, according to bankruptcy documents. Star sources suggest that Lipson is seeking that money from both Zaretsky and Rosenthal — but the only public record of her claim is on Zaretsky’s bankruptcy statement.

The Star sent letters, emails and called Rosenthal over the past three months. His office in North Toronto is closed up tight. At his home in Teddington Park near Yonge Street and Lawrence Avenue, nobody came to the door. According to text messages Rosenthal has recently sent one of his “investors,” he is planning to sell his Arizona home to pay debts.

“I am sorry I shattered our 59 years friendship,” Rosenthal wrote to Levine last December. “I am working on acquiring the Phoenix home, then sell it to repay you FIRST.” Rosenthal said in his email to Levine that the entire situation has “created a terrible toll on me,” for which he said he accepts “all the blame.” He said his wife is divorcing him, his children no longer speak to him, and the Canada Revenue Agency has seized his accounts.

Levine responded to Rosenthal, saying that he believes he has “parked millions of dollars” somewhere.

To which Rosenthal responded, “I have no money, hidden or in a bank. I wish it was true.

“I have only $210 in my name. I sold my old car in Phoenix to have money to live on and for my medical costs here for the past few months.”

Gilbert Sharpe, a former top Ontario bureaucrat, is out $40,000 — on the low end of investors in this story. He is not angry at Rosenthal, but he is disappointed in his friend. He notes that most of the people owed money are “not destitute.” Despite what has happened, Sharpe still has Rosenthal on file as his executor. He recalls with fondness how on a trip to Arizona with Rosenthal, Sharpe took ill, and Rosenthal got him treatment at the local Mayo clinic. “He was a real friend.”

Several investors have made complaints to police fraud squads. The investors say they have been told both that the case is too hard to prove, and that prosecutors are reluctant to take on a prosecution unless it is a “sure thing.”

For Israel, who enjoyed so many trips with Rosenthal over the years, it’s tough for him to reconcile what happened. He finds himself going back over things Rosenthal said.

“One time he said to me, ‘Peter, I’m an accountant, I don’t have a heart.’” In retrospect, Israel said there were signs that there would be trouble down the road.

“Looking back, sure, he was very Machiavellian,” Israel said. “I think he was foreshadowing with all the comments he made. His moral compass was screwed up.

“What bothers me now is, why the f—k didn’t I see it coming?”