The average decline in fertility among these recent cohorts relative to the cohorts preceding them by 20 years was 0.25 births. Of this decline, 0.09 births, or 37 percent of the gap, is statistically accounted for by increased childlessness in the later cohort. The remaining 0.16 births, or 63 percent of the gap, is accounted for by declines in fertility among the parous.

A similar analysis can be used to decompose differences across districts in India, where the difference to be decomposed is across districts for women born in the same set of years, with two groups of districts defined by having the lowest and highest cohort fertility rates. Unsurprisingly, given panel B of Figure 5, almost all of this difference—94 percent—is accounted for by the difference in fertility among the parous. Differing patterns of childlessness account for only 6 percent of the gap between high-fertility and low-fertility districts.

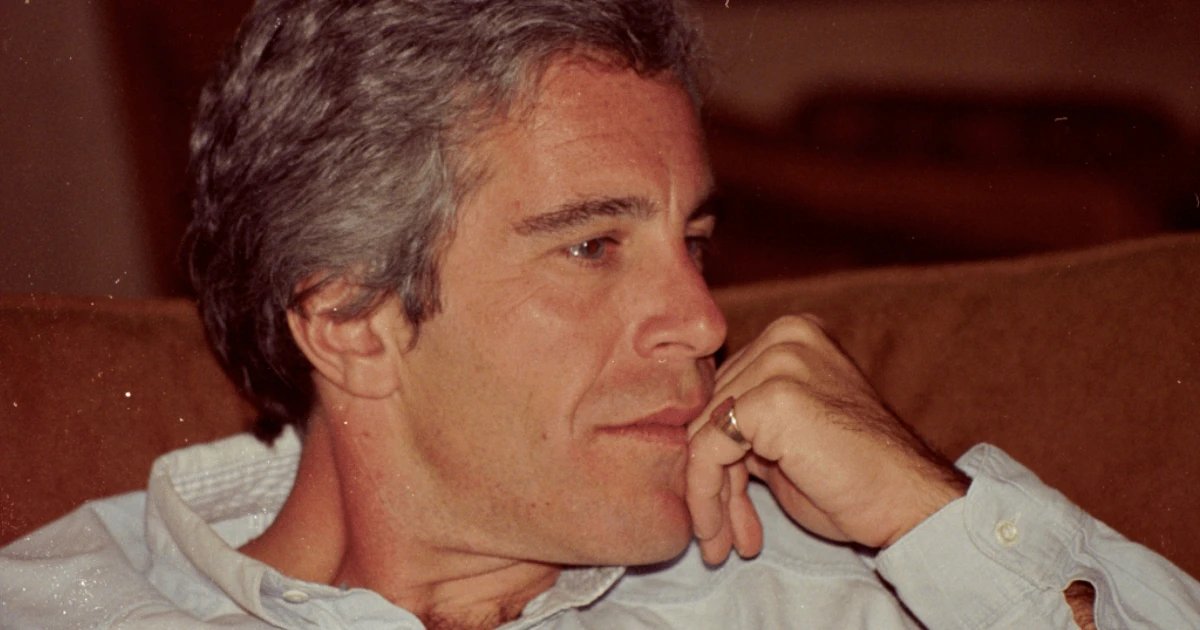

That is from a new and useful JEP survey article by Michael Geruso and Dean Spears. The main concern of the authors is whether we can ever expect a fertility rebound.