TUCSON, Ariz. — A Q-tip, a tissue and a pizza crust.

To investigators, this seemingly innocuous trash was DNA-laden treasure, helping crack the cases of the University of Idaho murders, the Golden State Killer and the Gilgo Beach slayings, according to authorities, using a forensic tool called investigative genetic genealogy.

Investigators in the Nancy Guthrie case hope that science can point to a suspect. But there are challenges.

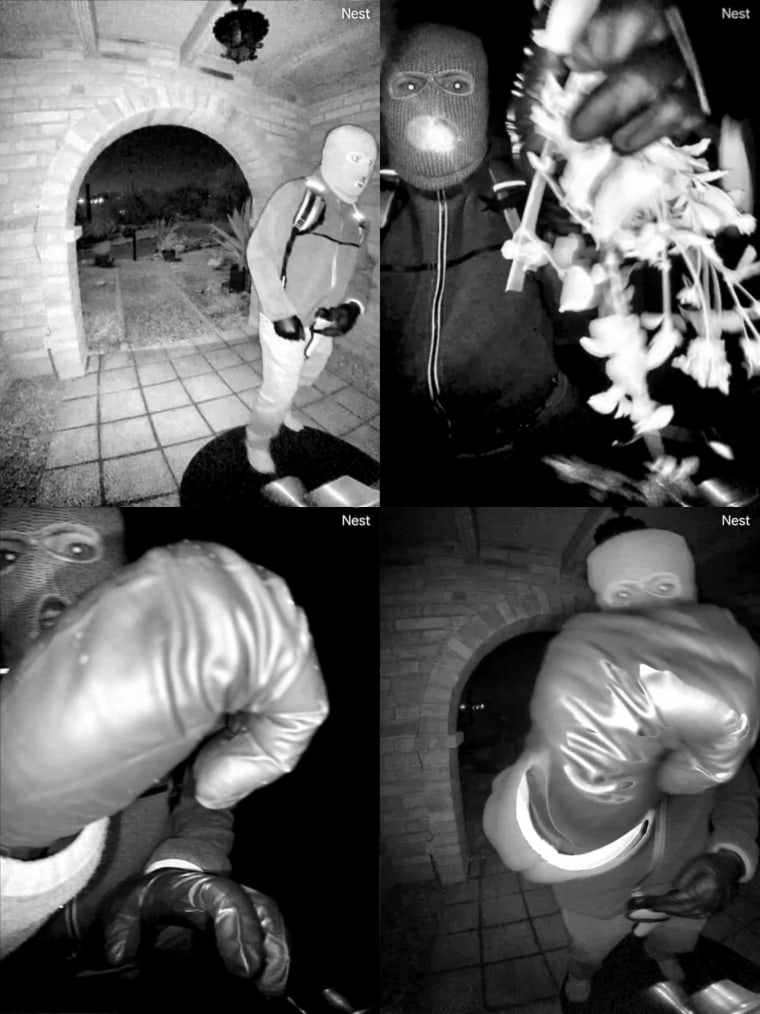

Guthrie, the 84-year-old mother of “TODAY” co-host Savannah Guthrie, was reported missing on Feb. 1. It’s been three agonizing weeks since her disappearance, and authorities haven’t publicly identified a suspect or a person of interest. Officials have cleared the Guthrie family as potential suspects, Pima County Sheriff Chris Nanos said.

Nanos, whose agency is leading the investigation along with federal and state partners, said last week that mixed and partial DNA was found at Guthrie’s home. Mixed DNA is a forensic sample that has more than one person’s genetic material.

More coverage of Nancy Guthrie’s disappearance

Some of that DNA that was found at the home doesn’t belong to Guthrie, her family or anyone who worked at the residence, Nanos said.

“We believe that we may have some DNA there that may be our suspect, but we won’t know that until that DNA is separated, sorted out, maybe admitted to CODIS, maybe through genetic genealogy,” Nanos said Tuesday, referring to the Combined DNA Index System, the FBI’s DNA database of convicted criminals.

But on Friday, he told NBC News the lab that received the DNA reported “challenges” with the sample. He did not elaborate on what the challenges are.

“We listen to our lab, and our lab tells us that there’s challenges with it, and we understand those challenges, but our lab also knows that the technology is moving so fast and in such a frenzy that they think some of this stuff will resolve itself just in a matter of weeks, months or maybe a year, to allow them to do better with, say, a mixture of that kind of thing,” he said.

Nanos said he’s “hopeful” the samples will get to a point where they can be submitted for investigative genetic genealogy or entered into CODIS, but “we’re not there yet.”

The sheriff’s department said in a statement Saturday: “As with any biological evidence, there can be challenges separating DNA, etc. There are currently no updates regarding this process.”

Investigative genetic genealogy, or IGG for short, is a process in which unidentified DNA evidence is turned into a digitized DNA profile. It’s then entered into ancestry databases to find relatives, build family trees and narrow down the person behind the DNA. It’s been used to solve long-cold cases, identifying unknown victims as well as killers.

The issue Nanos mentioned could be with the DNA sample itself or with the investigative genetic genealogy process, said Barbara Rae-Venter, a genetic genealogist who helped solve the case of the Golden State Killer in 2018 using this technique.

She said the sheriff’s comments suggest the DNA ratio has too high a proportion of victim DNA.

Colleen Fitzpatrick, an American genetic genealogist, said when it comes to mixed DNA, the suspect has to be the major contributor.

“Suppose you have a mixture and it’s 90% Nancy’s and 10% somebody else’s, that might not be enough for the lab to go forward and get enough markers and make the identification,” Fitzpatrick said. “If it’s 50-50, it’s hard to separate. Ninety-10, you can separate that. Probably also the question is not only separate, do you have enough DNA to work with anyway?”

The lab that authorities are believed to be using in the Guthrie case did not respond to a request for comment.

Challenges with IGG in Guthrie case

There are several challenges that investigators and genetic genealogists may face in this case.

But mixed DNA, which is often found at crime scenes, can often still yield helpful information, according to CeCe Moore, the chief genetic genealogist at Parabon, a Virginia lab specializing in forensic genetic genealogy.

“We’ve had success with a lot of cases with mixtures,” she said. “But it does take a little more time, because there’s an extra step. After that profile is created that we need for genetic genealogy, then they have to have the bioinformatics scientists work on that file to extract out the suspect’s DNA.”

Moore said the discovery of mixed DNA makes her “hopeful,” because “that does seem more likely that it could be definitively tied to the kidnapper in this case.”

Nanos has previously said that blood was found on the porch outside of Guthrie’s home that tested positive for her DNA.

It takes about a day or two to build a DNA profile — then “there are leads immediately,” said David Mittelman, a genealogist and the CEO of Othram, a forensic laboratory in Texas.

“In the worst-case scenario, it’ll connect you to a very close relative, and the best-case scenario gets it to your person,” he said.

IGG can also give other information such as biogeographical ancestry, meaning where the person was from historically, and connect it to large family groups in certain parts of the country, Mittelman said.

Moore says the speed of getting a hit with this process depends on race and ancestry.

“If the person of interest, in this case, has deep roots in the U.S. and is a white person, they could be identified in minutes or hours,” Moore said. “The vast majority of the people in the databases we have access to have primarily northwest European ancestry and deep roots in the United States.”

But she said there’s far less representation in databases of those with recent immigrant ancestry or those born outside of the U.S.

“If it’s somebody who doesn’t have connections to the U.S. in their tree in more recent generations, then it could take much longer,” Moore said.

Such was the case in identifying Bryan Kohberger, who killed four University of Idaho students in 2022. It took several weeks because he had recent ancestors from Italy.

Record access is also challenging for certain racial backgrounds, including African Americans.

“You get brick-walled at emancipation,” Rae-Venter said. “The actual written records of those marriages and deaths, which is what we’re normally using when trying to build these trees, there are no records once you hit the slavery wall. You can’t get any further back than 1863.”

Access to databases

Then, there’s the issue of how many profiles genetic genealogists can compare against.

They are limited to less than 2 million profiles to sift through — even though over 50 million people have taken direct-to-consumer DNA tests, Moore said.

This is because major companies such as Ancestry DNA and 23andMe, popular ancestry tracing sites, have barred law enforcement from accessing their databases to protect user privacy. However, those records can be requested by law enforcement and those companies can be compelled by court order or search warrant. The databases they can use are GEDMatch and FamilyTreeDNA, which have opt-in capability allowing law enforcement to compare against profiles.

“The two databases that we’re allowed to use are two of the smallest databases. If we could be using Ancestry or 23andMe or even MyHeritage, those databases are huge. You’re talking about 10, 20 times as many people,” Rae-Venter said.

“If you’re working on something like the Kohberger case or the Nancy Guthrie case, suddenly time is really important. … It’s adding time to what was already a very time-onerous procedure,” she said of the database limitations.

While the DNA samples in the Guthrie case don’t appear to be ready yet, experts are optimistic.

Rae-Venter said IGG has been around since 2007, back when it was used more commonly for unknown parentage cases.

One of its first uses in a criminal case was to catch the Golden State Killer, Joseph James DeAngelo, in 2018. In 2020, he was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole after pleading guilty to 13 counts of murder and 13 rape-related charges.

“Back when we did the Golden State Killer, there were virtually no tools to analyze the match information that you were getting, and now there’s just all kinds of really sophisticated tools to do that,” Rae-Venter said.

One of the advances is being able to work with tinier amounts of DNA.

“Back when we were doing that, you needed typically around 200 nanograms of DNA. Now, I actually did a case with, I think we had 25 picograms, so it was basically 1,000-fold less DNA,” she said.

She’s optimistic that if enough DNA is collected, it can solve the Guthrie case.

“Assuming that they were able to get some decent DNA out of it, they should be able to identify a potential suspect. The issue is just how long it’s going to take,” she said. “But ultimately, you should be able to solve the case.”

Marlene Lenthang reported from Los Angeles and Erin McLaughlin and Liz Kreutz from Tucson.