Frank Gehry once had a cameo in The Simpsons in which he designed buildings by scrunching up pieces of paper. There was a bit more to it than that, but from Prague to Panama City, his scrunched contours were instantly recognisable, expressed in an exuberant parade of buildings that cranked and slumped as if hit by a wrecking ball, or crashed and whirled like dervishes, defying laws of gravity and structural logic. Though Gehry, who has died aged 96, came of age in the era of modernism, it was as if he were physically incapable of drawing a straight line.

In his prime, Gehry’s architecture was a rebuff to modernist imperators such as Mies van der Rohe and his po-faced injunction, “less is more”. The American postmodern theorist and architect Robert Venturi turned it on its head, quipping “less is a bore”. It summed up the maximalist Gehry perfectly.

As the millennium loomed, he changed the game with his 1997 design for an outpost of the Guggenheim modern art empire in the unfashionable northern Spanish city of Bilbao. Grappling with post-industrial decline, its unlikely recovery was catalysed by a building of exhilarating complexity sheathed in an epidermis of 33,000 wafer-thin sheets of titanium that shimmered like rippling fish scales. With gallery spaces as expressive as the works they were designed to house, this was no neutral backdrop for art.

Set on a prominent waterfront site on the River Nervión, the Guggenheim became an instant icon, propelling Gehry, then in his late 60s, into the “starchitect” firmament, an epithet he affected to despise. And as its backers had hoped, it also transformed Bilbao’s wider civic fortunes, attracting 1.3 million visitors in its first year and begetting the “Bilbao effect”, which became shorthand for uplift through cultural tourism predicated on “iconic” architecture.

Bilbao was followed by the 2003 Walt Disney concert hall in Gehry’s adopted home town of Los Angeles, conceived as a clutch of stainless steel-clad volumes resembling billowing sails or giant metal shavings. He had urged his client to use stone, but they wanted a Bilbao. The timber-lined auditorium was warm and intimate, akin to being inside a musical instrument. Even the organ bore Gehry’s imprimatur, its scrum of pipes like a box of exploding french fries. For Gehry, whose family had relocated to Los Angeles from his birthplace of Toronto when he was 17, it represented the culmination of a long and formative relationship with the city.

The dynamic forms of his buildings were achieved through an ingenious yet laborious modus operandi involving the creation, in the first instance, of handbuilt models. These were then digitised using computer software capable of modelling complex curves, originally designed for use in the aerospace industry. Sculpture, in effect, became architecture, always striving for effect. Anything was possible.

As computers liberated form-making, architecture became increasingly – and often preposterously – uninhibited. Throughout the 90s and 00s, architects and their patrons strove to outdo each other, with Gehry leading the charge, through projects such as the Dancing House in Prague, nicknamed “Fred and Ginger”, where a pair of disparate towers conjoin in a twirling, balletic embrace, and the Jay Pritzker pavilion in Chicago’s Millennium Park, an outdoor amphitheatre framed by a halo of torqued stainless steel ribbons.

But as time wore on, in the effort to emulate the success of Bilbao, Gehry became fixated with chasing ill-conceived museum projects around the world. Extending its purview to the Middle East, in 2006 the Guggenheim commissioned him to produce an Abu Dhabi satellite, which has been dogged by delays and is slated to open only next year, two decades after its conception. “It was suggested that the huge budgets had raced past a clear idea of what the building would mean culturally or even what kind of artwork it would hold,” wrote Christopher Hawthorne in the Los Angeles Times.

Seattle’s over-egged Experience Music Project (since 2016 known as the Museum of Pop Culture) proved a wincing disappointment, while the 2014 Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, designed to accommodate the collection of French business magnate and art collector Bernard Arnault, is a bloated car crash, with some appallingly shoddy workmanship. By then, Gehry was also designing luggage, yachts and cognac bottles, a side hustle that began more prosaically with furniture made from layers of corrugated cardboard.

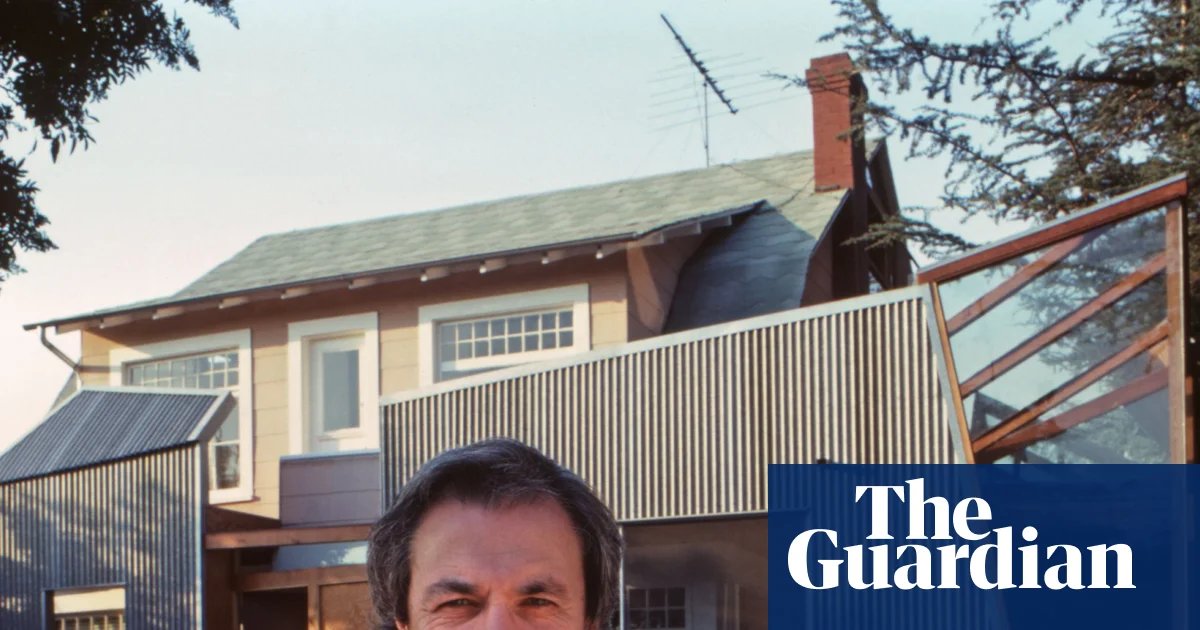

Such late-career hubris was a long way from the project that first made his name, his own house in Santa Monica, California, a two-storey pink stucco dwelling which he bought in 1977 and then proceeded to eviscerate and augment by collaging in bits of corrugated metal and chain-link fencing. “I was trying to use the dumb, normal materials of the neighbourhood,” he said at the time. Imbued with an edgy, gritty populism, his early work drew parallels with the art practice of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns.

LA provided the scope and momentum for experimentation as Gehry gradually found his rhythm in a frontier town of sprawl and ad-hocism. Revelling in exaggerated geometries and juxtapositions, a 1980 house for film-maker Jane Spiller featured a plywood interior encased in a carapace of corrugated metal. Where the timber sporadically broke through the external walls “the house felt like the architectural equivalent of a couple quarrelling in the kitchen”, wrote the American architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff.

Though Gehry built extensively in Europe, especially in Germany, with housing towers in Düsseldorf slouching like dissipated drunks, and a design museum for the Vitra furniture campus, which marked his transition from industrial bricolage to more poised, sculptural spectacle, the UK proved more resistant to his charms.

In 2003 he designed a Maggie’s Centre for the Ninewells hospital in Dundee, part of a network of drop-in centres for those affected by cancer. Surprisingly sober and simple, it’s modelled on a traditional Scottish “but and ben” dwelling, with a white cottage topped by a folded metal roof, like a piece of origami.

Latterly, he was involved in terraforming the environs around Battersea power station, designing silos of luxury housing that for all their cleverness feel distinctly formulaic. He was also invited to devise a Serpentine pavilion, London’s annual architectural fête d’été, reconceptualising it as a whirlwind in a lumber yard.

In a career that spanned 60 years, Gehry became a quintessential grand old man of architecture, apt, on occasion, to yell at clouds, as the world changed around him. At a 2014 press conference in Spain, on the occasion of him being garlanded with yet another award, when accused of designing “spectacle architecture”, he silently flipped his audience the finger. He later apologised. He also declared that: “In the world we live in 98% of what is built and designed today is pure crap. There’s no sense of design, no respect for humanity, just damn buildings.”