The glaring fundamental barrier between Beijing and the West remains the incompatibility between the absolute authority of China’s Communist Party and the societal accountability of democratic institutions — including Canada’s.

A purge of senior generals and deepening concern about China’s wobbling economy have had global Beijing-watchers sniffing for hints of regime fragility.

Skepticism about President Xi Jinping’s hold on power only intensified this month after China resorted to a 20-year prison sentence to silence 78-year-old democracy advocate Jimmy Lai.

Was that a message of deterrence or desperation?

The swirling dramas are noticed here in Canada.

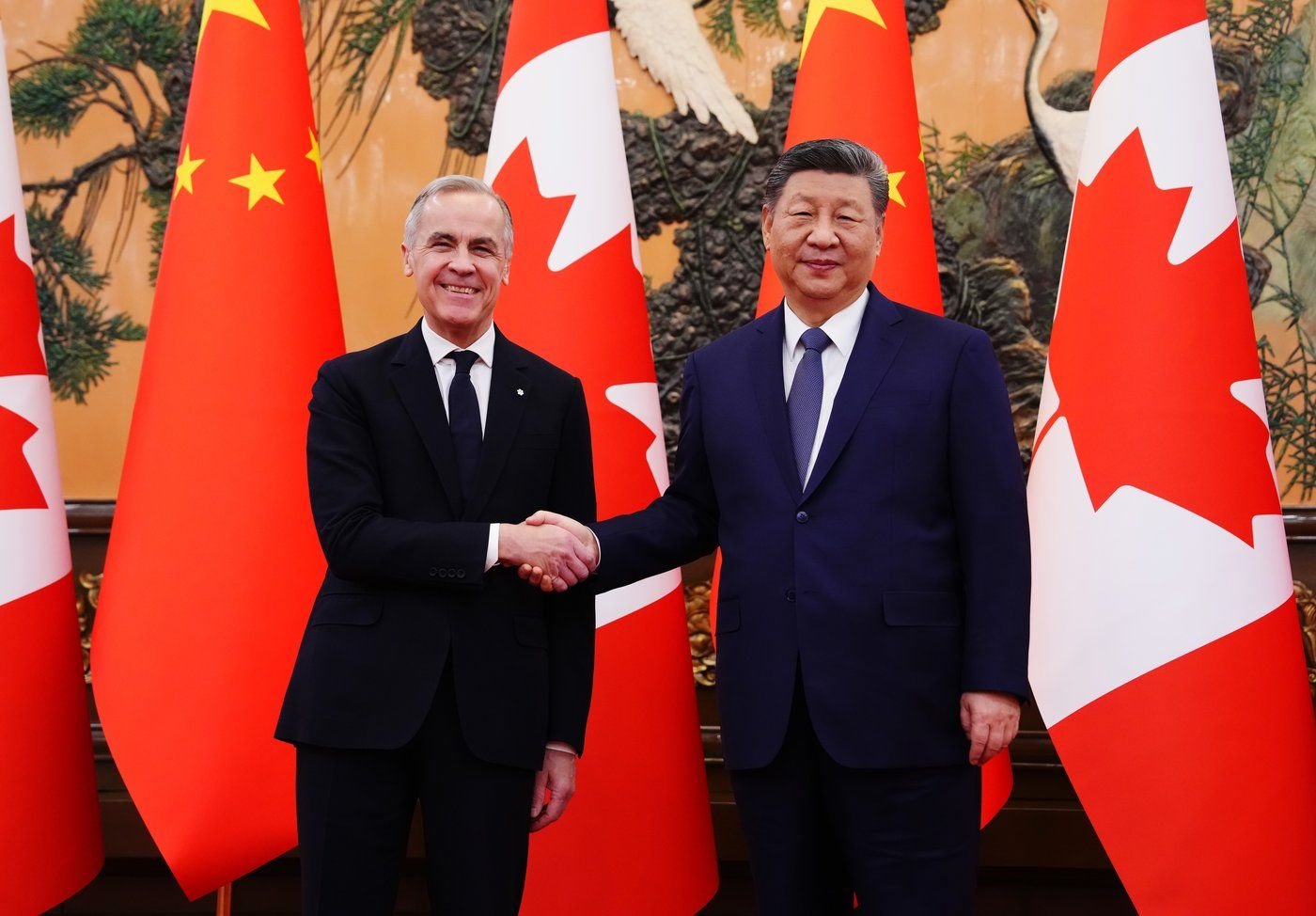

Mark Carney’s description of our new rapport with China as a “strategic partnership” was already causing unease among Canada’s intelligence community and Canadians of Chinese, Tibetan, Uyghur, and Taiwanese background.

They worry there is now an understanding that Ottawa will consciously ignore Beijing’s espionage and influence operations in Canada, its repression of Chinese expats, and its flouting of justice both in China and internationally.

This is on top of doubts about claims that Canada will expand the meagre four-per-cent of our commodity exports that go to China. Based on experience dating back to Jean Chretien, who despite his best efforts failed to grow our market share in China, it is unlikely that China represents economic inroads for Canada. Beijing will never allow imports to compete fairly against its own domestic goods, especially with China’s economy languishing under Xi Jinping’s anti-market statist policies.

Another factor is that any agreements signed by China’s political institutions — including the very ministries with whom Ottawa is negotiating MOUs — are routinely overruled by powerful officials in the military and security agencies. As Chairman Mao once put it, “political power grows out of the barrel of a gun”.

China’s People’s Liberation Army, Navy, and Air Force do not answer to the state or its constitution, but to Chinese Communist Party (CCP) masters. President Xi Jinping’s most powerful role is probably chairmanship of the Central Military Commission.

Last month Zhang Youxia, the senior official under Xi in the Military Commission, was the latest general to be abruptly removed from office, with little explanation. That seven-man commission is now reduced to just two: Xi and General Zhang Shengmin — and there are indications Zhang may not last long.

The purged generals were felled by vague accusations of corruption. In the world of abruptly dispatched Chinese officials, corruption charges are a catch-all term for the losers in political factional struggles.

Speculation has erupted among China “experts” over the demise of these generals. Will they be replaced by sycophants who fulfill Xi’s determination to cement his place in history by “liberating” Taiwan in 2027, before he retires from office? Or perhaps the removals have left military leadership so weak that plans to annex Taiwan must be deferred.

Are the purges a sign of Xi’s absolute power? Or perhaps he is actually politically vulnerable because party factions that he has sidelined since taking power in 2012 have been setting the stage for their own military loyalists to repeat the sort of coup that overthrew the Maoists 50 years ago, restoring leaders who had been sent into the wilderness in the Cultural Revolution.

Whatever is really going on with Xi’s grip on power (and officials in Washington and elsewhere are watching very closely), the glaring fundamental barrier between Beijing and the West remains the incompatibility between the absolute authority of China’s Communist Party and the societal accountability of democratic institutions — including Canada’s.

This is not simply a case of divergent opinions over human rights or the role of sovereignty in relations between nations. Before we even begin negotiating the details of diplomatic or trade agreements, seeing the Canada-China relationship as a “strategic partnership” first requires us to believe that we can have reciprocal, fair state-to-state relations.

And that requires buying into a myth, not reality.

Charles Burton is a former diplomat at Canada’s embassy in Beijing and a senior fellow at Sinopsis.cz, a global China-focused think tank based in Prague; committee member of Taiwan-based Doublethink Lab’s China Index.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by all iPolitics columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of iPolitics.