It is not an understatement to say that the modern beauty industry—the organic ideas born of it, the artistry within, and the web of humanity giving it a thrumming pulse—cannot stand without the transgender community. It’s not fabrication to say that brands have made millions from the endorsement and branding of trans creators, performers, models, and activists when a product or launch is involved. The inclusion of trans people in the beauty space is a necessary step for art, industry, and humanity—one that allows creatives, regardless of gender and entirely reliant on talent and vision, to leave their mark on the ecosystem that helped them self-actualize. Yet once the boardroom-pleasing profit reports are presented and the set lighting comes down, the trans community feels left out in the cold once again.

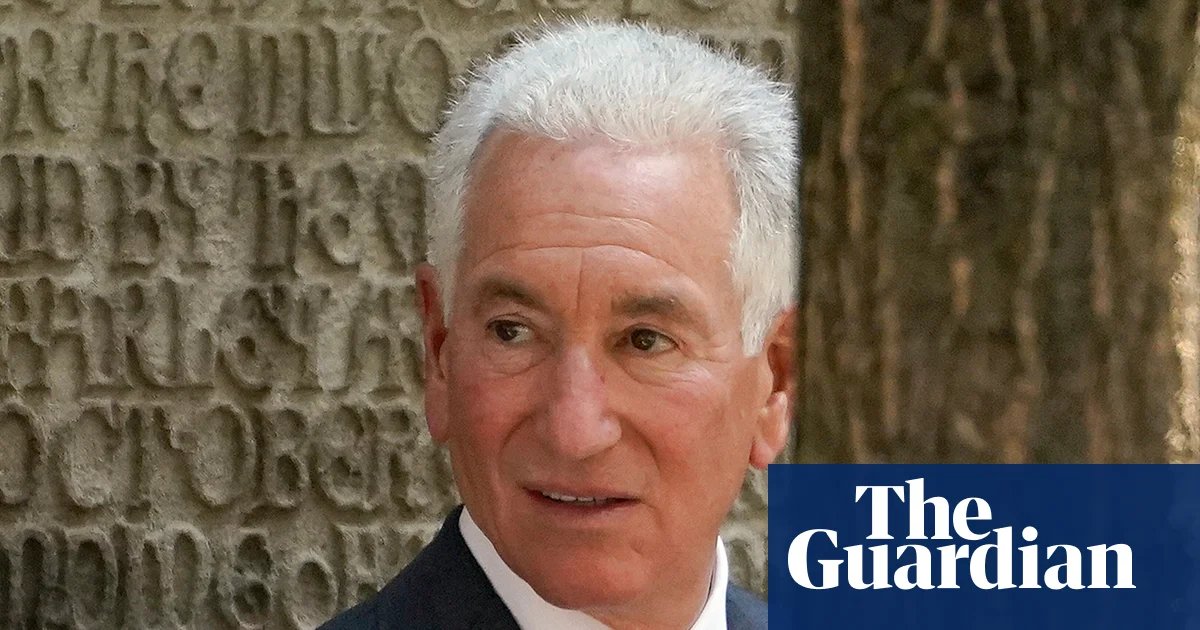

“The beauty industry is slightly ahead of the rest of the fashion industry when it comes to employing and supporting trans people, but that isn’t saying much,” says New York-based makeup artist Mical Klip. Following a tumultuous 2025, when access to basic needs like safe healthcare was swiftly and heavily restricted by the Trump Administration, the trans community has had to pull its weight more than ever to ask allies to #protectthedolls. Though beauty has long been a safe haven for said community, members are now asking more of it during this time of dire need.

The few trans creatives who achieve the dream of breaking into this industry (take Nykita Joy, for example—a content creator and makeup artist who boasts millions of social media followers) often feel overlooked by the space that once gave them direction amidst coming-of-age struggles in foreign bodies. “It was in the distance forced between me and beauty by the adults in my life that my love for beauty was born,” Joy recalls of her painful upbringing. “Then it was through the need for protection in a world that didn’t believe me worthy of said protection that honed my skills of this craft, using beauty as a tool for survival [over the years].” However, the resounding sentiment across the community today—though first sugared with appreciation for a morsel of representation—is that there is much more room for growth.

Beauty products and practices, from a gender-affirming fragrance to a new haircut, are some of the most transformative avenues for a trans person. The right acne treatment to battle hormonal flareups, hairstyling routine, or lipstick shade might offer that extra dose of confidence someone needs as they grow into themselves—at least, this is what we’ve found in speaking with these four trans people in New York City as they navigate their own deeply personal journeys. Beauty has been a saving grace in their lives, but the question is whether or not the industry is willing to return the favor.

Mical Klip

(Image credit: Courtesy of Isaac Anthony)

Klip wasn’t sure what they were looking for when they tried to imagine the type of person they wanted to become—that is, the gender they identified as, especially considering their career and the things they liked to do. Makeup and skincare were, and still are, major points of interest for the booked and busy makeup artist, whose work you can spot on Cole Escola, Iris Apatow, and everything from the Met Gala red carpet to digital Vogue features. You see, it was this dichotomy that made the artist hyper-aware of where they fit—or, perhaps didn’t—into societal gender norms.

“Like a lot of transmascs, there were aspects of femininity I loved and wanted to hold on to, but didn’t feel like they would be interpreted in the way I wanted,” Klip reminisces. Being someone who grew up loving makeup, aesthetics, and fashion—traditionally deemed “girly” things—and transitioned in their late twenties, it proved impossible to figure out the “kind of woman” they thought they wanted to become.

“It started to dawn on me as I cycled through different ways of presenting that there wasn’t going to be one that felt right, and that I had to look somewhere outside of woman-ness to feel like myself,” says Klip. Because beauty was already such an inherent part of the artist’s life—it paid the bills and served as a creative outlet—they needed to step away from the gendered looking glass they’d been conditioned to observe beauty through. “Ultimately, it was being around other trans people that allowed me to loosen my grip on a rigid idea of what being trans should look like.”

It started to dawn on me as I cycled through different ways of presenting that there wasn’t going to be one that felt right, and that I had to look somewhere outside of woman-ness to feel like myself.

Mical Klip

Makeup has never left the artist’s personal regimen (they still like to wear concealer and brow gel—Nars’ Radiant Creamy Concealer and Benefit’s 24-Hour Brow Setter Gel are their favorites), but it was their first buzzcut that made all the difference. “I found that buzzing [my hair] allowed me to see my own face in a way I hadn’t before,” they explain. “[It’s] a pretty clichéd move, but I still recommend it to anyone who’s tempted.”

Klip is proud of the work they’ve accomplished in their professional career, but wants to uplift the other trans talent they see vying for the same goals. “Black trans women in particular are responsible for so much of the beauty aesthetic that has become mainstream, and haven’t gotten the recognition and compensation they deserve,” they state. “I want to see more trans people everywhere in fashion [and beauty], but that isn’t going to happen until we address the economic barriers to breaking into the industry in the first place.” Calling for fair financial compensation and opportunity, Klip implores the beauty gods for a fairer industry that gives trans people a better shot at starting at all.

Nykita Joy

“I am the product of not being allowed access to gender-affirming care as a minor,” says Joy. The trans makeup artist and celebrated content creator—whose laundry list of achievements includes SFX (special effects) artistry in New York theater productions, walking runways at New York Fashion Week, and collaborating with major beauty and high fashion brands through her viral content—finally feels as if she’s found herself after a lifetime of infighting.

Joy laments the time, resources, and money lost to medically transitioning as an adult when her true sense of self was one of her first conscious thoughts. “By people who claim to know what’s best for children, I was forced into a body that I did not consent to—a body I begged daily, in between begging for death, not to have to live in,” she confides. Born into a conservative Southern household to a loving mother unprepared to offer her daughter the life she needed and an abusive father, Joy faced the horrors of an adolescence stripped of autonomy and endangered by conversion therapy and closeted men. “Transition was my liberation,” she explains.

Transsexual survival isn’t marketable [… and] real impact often isn’t going to be brand-safe. Impact implies a stance.

Nykita Joy

The multi-hyphenate’s first sense of gender-affirmation was within fashion and makeup—a foreshadowing for her bright future—which was deemed “contraband” in her father’s house. During his “routine shakedowns,” teenage Joy would often return home to a doorless bedroom, her forbidden clothes and makeup strewn across the floor. “Through immense restriction, my beauty platform inevitably exploded—like a seed bursting through concrete,” she recalls. “And much like that seed, nothing will prevent me, or my platform, from growing.”

At the age of 21, Joy underwent sexual reassignment surgery—a gift she credits for her thriving life today. “My transition has been the physical manifestation of my impulse to shield my younger self from the circumstances she could not, and would not, consent to,” she states. It’s because Joy knows this painstaking fight personally that she co-founded Strands for Trans, a nonprofit organization that connects anyone in crisis with gender-affirming, global beauty services. “Something as simple as a haircut can be one of the most affirming acts of self-reclamation available to someone at any stage of their transition,” Joy explains.

Her ask of the beauty industry? That they reciprocate this energy for the trans community that makes up so much of its demographic. “The beauty industry consistently fails trans individuals, particularly trans women, while simultaneously benefiting from the visibility of the nonbinary community,” she states. “In this current political landscape, the trans community is in crisis… [we are] screaming for you to hear us.” Joy calls for action in the form of lifesaving mutual aid—“things like rental support and relief from housing insecurity, access to hormones, legal fees, food in the fridge…”—basic necessities harbored from trans individuals.

“Transsexual survival isn’t marketable [and] real impact often isn’t going to be brand-safe,” Joy adds. “Impact implies a stance.”

Quinn Tommy Herbert

Quinn Tommy Herbert, a 26-year-old fashion stylist and model in New York City, recently married the love of her life while clad in an LBD during a chic civil ceremony—something she might have only dreamed of growing up as a queer boy in Iowa. “So many moments that comprise my coming of age were inherently trans, despite my lack of vocabulary surrounding them,” she reflects. Throughout her childhood, Herbert felt aligned with “boyhood” to an extent—loving video games, science fiction, and fantasy like the others in her class. However, her interest in fashion and beauty began to simultaneously bloom in a way that felt very “look-don’t-touch.”

“I became fascinated with pop culture, design, and nightlife—all unreachable to my Midwest station in life,” she explains. While her high school teachers droned, Herbert’s head swam with daydreams of Galliano-era Dior and Pat McGrath’s next lipstick kit launch (Vermillion Venom was a personal favorite, she shares), planting roots for the woman we see today. “I wore Fragonard Diamant at the age of 15,” Herbert laughs. “Let the record reflect it is deeply transgender to be a 15-year-old, androgynous gay boy wearing a rich gourmand perfume in an Iowan high school.”

Allow trans people into rooms and positions where decisions are made. We’re not just consumers, we are innovators.

Quinn Tommy Herbert

Fragrance was one of the first sources of gender affirmation that the stylist found in beauty. In fact, Herbert can categorize the eras of her transition with it: Diamant in her Midwestern high school era, Mugler’s Angel Nova for her first years in New York, and Rabanne’s 1 Million Elixir for the period of change she’s currently experiencing. Having adjusted her hormone therapy regimen for potential family planning, the stylist is accepting the change her body, skin, and hair are undergoing once again.

“[It’s] made me relinquish control over needing to appear overtly feminine,” Herbert explains. “But now more than ever, I am constantly reminded of the power of a smoky eye and a bit of lip liner to make me feel aligned,” she adds. Once Herbert decides to resume HRT, she plans on finding a new scent to mark her latest chapter.

Like Joy, Herbert found comfort in a mother who embraced her role as a girl mom. “My beauty routines have ebbed and flowed with lessons from the femmes in my life,” she explains, having learned the “curly girl method” from her mother and two best friends to style her bouncy spirals, and honed her makeup skills thanks to her favorite YouTubers (shoutout Nikki Tutorials). It’s these learnings that served as the basis of her career today—a vibrant mixture of styling work (recently having assisted stylist Patti Wilson for Cher and Irina Shayk) and modeling, boasting campaigns and catwalks with Milk Makeup and Kim Shui, to name a few.

The multi-hyphenate echoes the same sentiment as the rest: to protect the dolls, not only by prioritizing representation, but also with funding and job security. “The beauty industry can focus on booking trans talent and artists… Do not simply attempt to profit from our image,” Herbert firmly states. “Allow trans people into rooms and positions where decisions are made. We are not just consumers, we are innovators.”

Zhi Lu

The other half of Herbert’s wedding party is none other than Zhi Lu, a 28-year-old tattoo artist based in Brooklyn, NY. While reveling in nuptial bliss, Lu is also taking a moment to reflect on his upbringing thanks to a memory box full of baby photos his mother recently shipped from China. “In some ways, those early life moments were strangely the most gender-affirming, or rather, the least gendered time of my life,” he reflects, parsing through prints of the little girl clad in her older cousin’s “boy” clothes. “The idea that ‘boys wear blue and girls wear pink’ had yet to infiltrate the insular small town that I grew up in, and remained a distant aesthetic of Americana,” he explains.

Clothes, as evidenced, did not inform Lu’s gender identity as the artist began to grow into himself. In fact, it was the cultural significance of hair and his own interest in skin—caring for it and tattooing it—that made marks on Lu’s sense of style and being. “I realized through the course of HRT that I was trading my good skin for a deeper voice and a more muscular shoulder frame, and hormonal acne was really no joke,” he shares. However, his hair is a completely different story—and one that goes deeper than aesthetics.

Queer haircuts are one of my favorite social phenomena to observe. They are usually expressions of resistance and non-conformity… a covert signal to others who might share similar identities and lived experiences.

Zhi Lu

After realizing his trans identity, Lu has cycled through phases of shaving and growing his hair to feel more aligned with his masculinity. “Queer haircuts are one of my favorite social phenomena to observe,” he states. “They are usually expressions of resistance and non-conformity… a covert signal to others who might share similar identities and lived experiences.” One of the styles from early in his transition that stuck—making him feel aligned with more than just his gender—is symbolic braids.

“It is gender-affirming, not in the way that it adheres to a Western and contemporary imagination of masculinity—[it’s] affirming in the way that my braids call me to connect with my ancestors,” he explains. His style, clipped close around the face and before falling into two long braids at the nape, has a double meaning when worn by Lu. “Like many indigenous populations, men had worn their long hair in pride, as their wisdom and age are displayed through their well-tended long braids,” he explains. His adoption of this style breathes new life into the ancestral traditions Lu cherishes.

It’s the care and keeping of his hair that has allowed him and Herbert to trade maintenance hacks—she giving him styling tips for his growing hair, once partly shaved and now growing into a short crop. “My wife shared with me the styling paste she used to use for her hair [in her youth] when she had shorter hair,” Lu explains. “How magical it is, passing down gendered knowledge in a T4T relationship.”

Lu concludes by echoing the grievances of his community and calls for a stronger sense of unity—especially since, as he points out, most beauty products and services are inherently gender-affirming. “Your BBL, waxing appointment, and estrogen topical cream for menopause are all 100% gender-affirming procedures,” he states. “So let’s have some solidarity.”