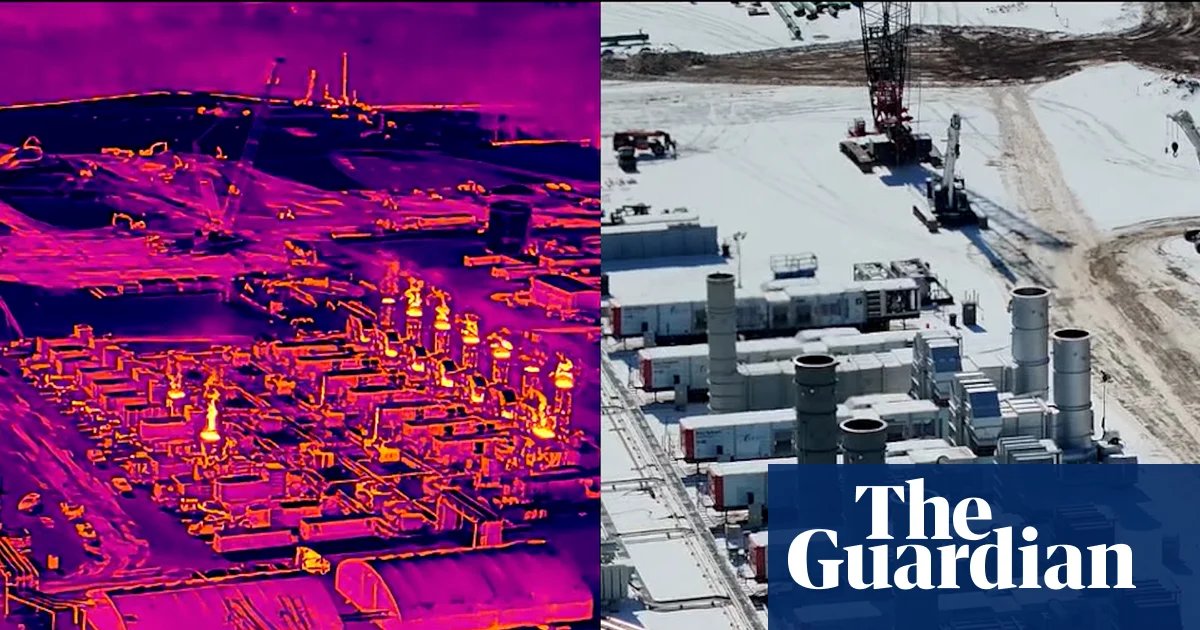

Elon Musk’s artificial intelligence company is continuing to fuel its datacenters with unpermitted gas turbines, an investigation by the Floodlight newsroom shows. Thermal footage captured by Floodlight via drone shows xAI is still burning gas at a facility in Southaven, Mississippi, despite a recent Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) ruling reiterating that doing so requires a state permit in advance.

State regulators in Mississippi maintain that since the turbines are parked on tractor trailers, they don’t require permits. However, the EPA has long maintained that such pollution sources require permits under the Clean Air Act.

Any exemption for these machines “could leave these engines subject to no emission standards at all”, the agency wrote in a January final ruling.

However, thermal images captured by Floodlight – and analyzed by multiple experts – show more than a dozen unpermitted turbines still spewing pollutants at the plant nearly two weeks after the EPA’s recent ruling.

“That is a violation of the law,” said Bruce Buckheit, a former EPA air enforcement chief, after reviewing Floodlight’s images and EPA regulations. “You’re supposed to get permission first.”

xAI, which is seeking permits for dozens more turbines in Southaven, did not respond to multiple requests for comment. The EPA, which under Trump has initiated a record-low number of enforcement actions, declined to answer questions about the turbines at Musk’s AI facilities and referred to local authorities on permits.

The first and only public hearing on the matter is scheduled for Tuesday 17 February, and the public comment period is still open.

The Trump administration has made AI a priority, but as datacenters proliferate across the country, regulators are struggling to keep pace with the industry’s increasing reliance on custom-built or ad hoc power sources and their public health impacts on surrounding communities. And Southaven, where state regulators are at odds with federal guidance, is a prime example.

The turbines there help power Grok, the company’s controversial chatbot, and emit harmful pollutants linked to health problems such as asthma, lung cancer and heart attacks.

“The risk of living next to this type of power plant is well documented,” said Shaolei Ren, a UC Riverside associate professor who specializes in the health impacts of datacenters. “From the health perspective, we know that this is not good.”

Southaven residents have voiced concerns for months about the noise and pollution emanating from the 114-acre site that is largely hidden from public view – a site xAI is looking to expand.

“For them to be releasing so much pollution in such a populated area, not to mention that there are at least 10 schools within a two-mile radius of the facility, is really concerning,” said longtime resident Shannon Samsa. “It’s horrifying to me that we’re allowing this in our community.”

From Memphis to Mississippi

The Southaven turbine cluster is part of xAi’s rapidly growing footprint along the Tennessee-Mississippi border. That expansion began in the spring of 2024 in South Memphis, next to historically Black neighborhoods, which often disproportionately bear the brunt of pollution from nearby plants, with the construction of Colossus 1, which the company touted as the world’s largest AI supercomputer.

The Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC) released thermal images in April revealing that xAi had been operating more than 30 unpermitted gas-powered turbines at that site.

“We were hopeful that the health department would step in,” said Patrick Anderson, a senior attorney at the SELC. “That never happened.”

County officials in Tennessee maintained that the turbines did not require a permit despite longstanding EPA policy that they do. In July, amid local pushback, the county permitted 15 turbines for use at the Colossus 1 site.

On 15 January, the EPA reiterated its decades-old policy that such machines need a permit. By then, xAi had already built a second datacenter in the area, Colossus 2. To power it, the company parked 27 turbines just across the state line in Southaven, Mississippi, a diverse Memphis suburb with higher than average levels of air pollution.

“When you’re talking about these turbines, think of the jet engine,” said Buckheit.

Despite the EPA’s recent directive, Floodlight’s thermal imagery – analyzed by multiple experts – shows 15 unpermitted turbines in operation at the Southaven facility. Public records obtained by Floodlight show 18 of the 27 turbines have been used since November, at least.

“One might easily have expected, since this has been going on for some months, at least a stop-work order [issued from the EPA],” said Buckheit, who served during the Republican Gerald Ford and George W Bush administrations. He also said the EPA could refer the case to the Department of Justice.

“But apparently that didn’t happen.”

Playing by a different set of rules

An EPA spokesperson did not answer Floodlight’s questions relating to its enforcement options, instead saying: “EPA does not approve the operation of gas turbines at facilities, that would be the state or local air permitting authority.”

Indeed, air permits are traditionally handled by state agencies. However, according to its own website, the EPA is responsible for making sure these agencies comply with federal regulations, and “generally will take enforcement action” if a state government fails to “take timely and appropriate action”.

xAI “violated the Clean Air Act the first time, and now they’re gonna copy and paste and do it again”, said the SELC’s Anderson. “I maybe had some naive hope that the regulators who are most in the day-to-day business of implementing the Clean Air Act in Mississippi would do the right thing.”

In response to Floodlight’s questions, a spokesperson from the Mississippi department of environmental quality said the EPA’s recent rule leaves permitting decisions to state authorities.

“The turbines currently operating at the Southaven facility are classified as portable/mobile units under state law and therefore remain exempt from air permitting requirements during this temporary period,” they said. “Nothing in the EPA’s January 15 rule altered that determination under Mississippi regulations.”

Longtime resident Krystal Polk said she had no idea xAI was coming to Southaven until black fences were set up across the street from her house. The area, she said, was once quiet and serene, with an abundance of wildlife, but is now bombarded by ceaseless noise and pollution.

“I do feel like xAi is playing by a different set of rules,” she said.

Polk, who has asthma, said she was forced to empty out the home that’s been in her family for generations and cancel her plans to retire there out of concerns for her health.

“We are a casualty of the whole datacenter race,” she said. “I feel that my voice doesn’t matter.”

The spokesperson for the Mississippi department of environmental quality said the agency took public concern about emissions, noise and overall quality of life seriously, and though the turbines – in the department’s view – do not require permits, all “applicable air quality standards still apply”.

AI’s increasing thirst for fossil fuels

Despite lofty sustainability goals put forward by industry leaders, datacenters across the country are increasingly turning to fossil fuels to power the AI boom by using custom-built power plants like the ones seen in Southaven.

Roughly 75% of this power comes from natural gas, according to a recent report by Cleanview, which tracks clean energy and datacenter projects.

“Nearly every project we reviewed mentions renewables, hydrogen, or nuclear in its public announcements,” the author wrote, but renewables aren’t scheduled until 2028 or later.

And “nuclear is a decade away”, he said.

Now xAI is seeking to expand in Southaven, applying in January for a permit to operate 41 turbines at the site.

The facility could emit more than 6m tons of greenhouse gases and more than 1,300 tons of health-harming air pollutants every year, according to xAI’s permit application. That would make it among the largest fossil fuel power plants in the state. The company also bought property in Southaven for a third datacenter that, when completed, will make the Colossus cluster – spanning Memphis to Southaven – one of the largest datacenter complexes in the world.

“It would be devastating,” said Samsa, the Southaven resident. “No community in their right mind would want something like this in their back yards.”

Samsa, a physician’s assistant, had hoped to raise a family in Southaven, but the presence of xAi’s gas-powered turbines has made her and her husband reconsider. She has helped collect more than 1,000 signatures for a petition demanding Mississippi authorities shut down the plant.

“I don’t want my children to be growing up around such massive amounts of air pollution,” she said. “I don’t want them to have to live in a place where their health and their overall wellbeing is not considered over economics.”