Senator Bill Cassidy (R-La.) released a new report on how to modernize the FDA. It has some good material.

One of the greatest challenges innovators face, particularly small- and medium-sized companies, is that FDA’s process for reviewing new products can be an unpredictable “black box.” FDA teams can differ greatly in the extent to which they require testing or impose standards that are not calibrated to the relevant risks. The perceived disconnect between the forward leaning rhetoric and thought leadership of senior FDA officials and cautious reviewer practice creates further unpredictability. This uncertainty dampens investment and increases the time it takes for patients to receive new therapies.

Companies report that they face a “reviewer lottery,” where critical questions hinge on the approach of a small number of individuals at FDA. Some FDA review teams are creative and forward-leaning, helping developers design programs and overcome obstacles to get needed products to patients, without cutting corners. FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence (OCE), for example, is repeatedly identified as a model for providing predictable yet flexible options for bringing new drugs to cancer patients. OCE is now a dialogue-based regulatory paradigm that has facilitated efforts by academia, industry, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and others to develop new cancer therapies and launch innovative programs and pilots like Project Orbis, RealTime Oncology Review.

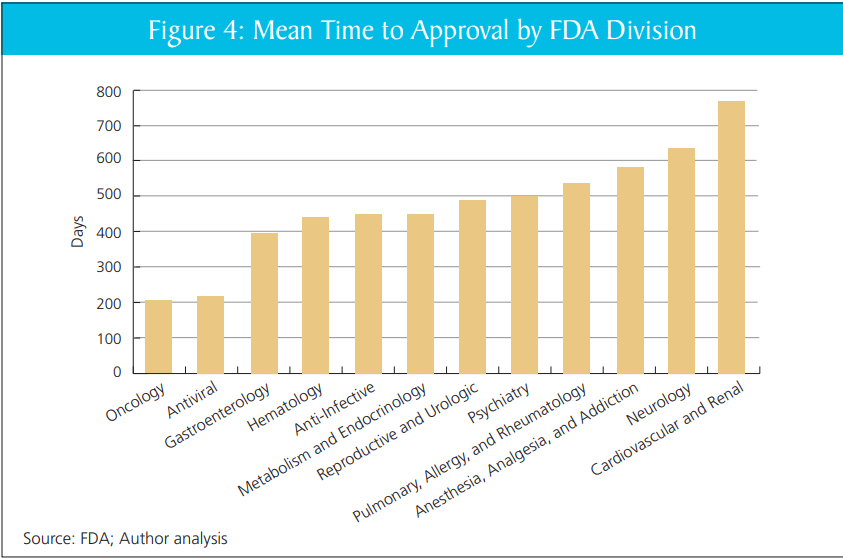

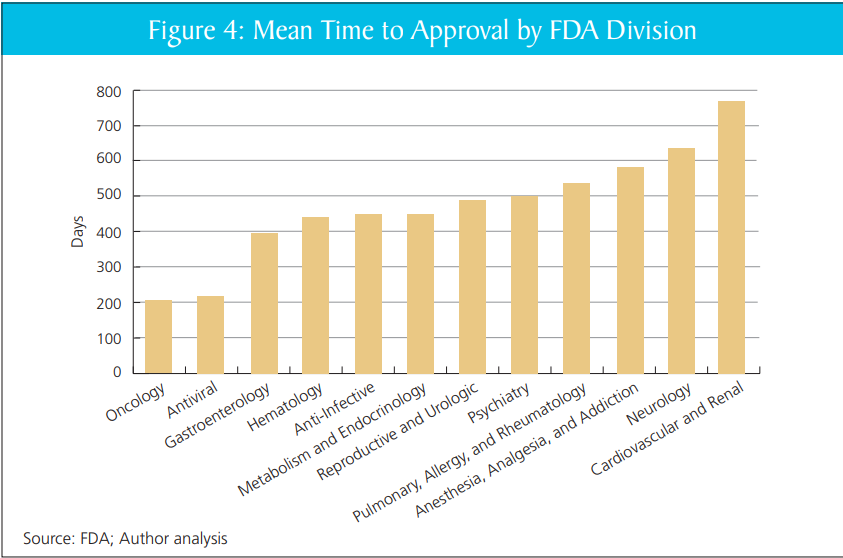

That’s quite right. In my report with DiMasi and Milne, we show that review times vary markedly within the FDA, across divisions, without clear cause. Put aside the big questions of FDA or no FDA–scaling the practices of the better-performing divisions would likely yield large gains.

Mike Doherty further asks the AI what Alex Tabarrok would think of the Cassidy report. It replies:

Strongest features: It correctly diagnoses FDA as a bottleneck to innovation, emphasizes “least burdensome” evidence, calls for streamlined pathways (505(b)(2)-style for biologics, biosimilar simplification), and worries about U.S. losing early-phase trials to other countries. This is very much in Tabarrok’s wheelhouse: regulation as a hidden tax on innovation and growth.

Weakest features: It rarely quantifies tradeoffs, almost never confronts the “invisible graveyard” of patients who never see therapies because of delay, and treats reforms as marginal tweaks rather than testing fundamentally different regulatory models (e.g., insurance-based approval, private certification, or sunset/experimentation with parallel regimes).

If you imagine this as a draft memo handed to Tabarrok, he’d likely say: “Good directionally; now add 50% more economics, 50% more quantification, and 100% more willingness to experiment with institutional competition.”

Yeah, pretty good.

Addendum: In other FDA news see also Adam Kroetsch on Will Bayesian Statistics Transform Trials?