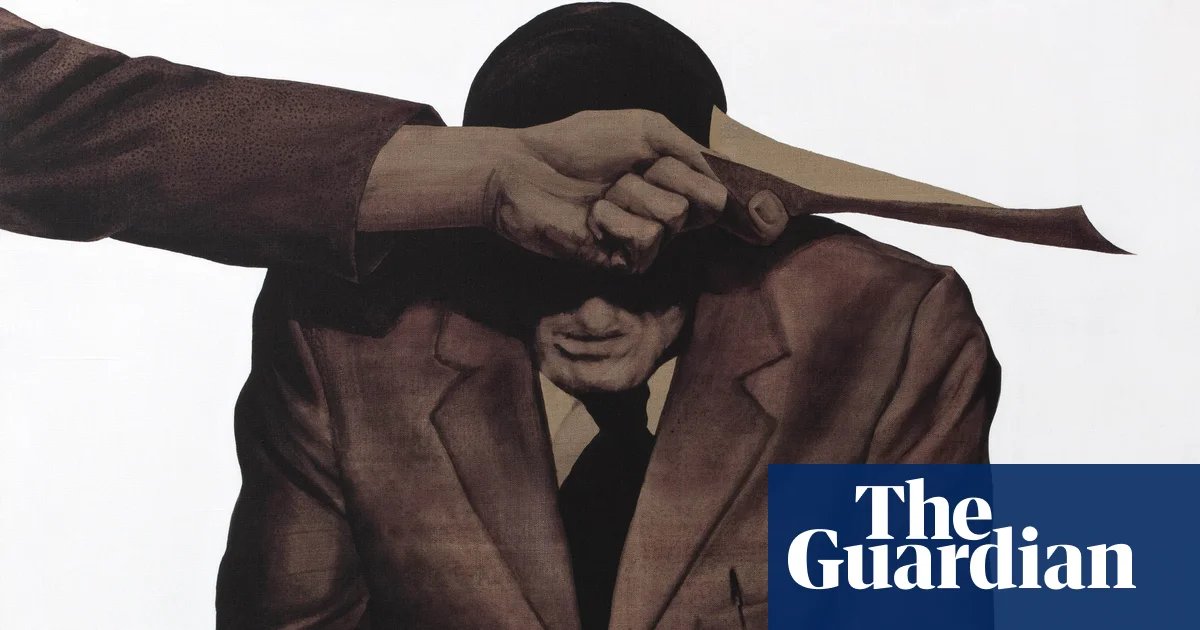

The Reina Sofía’s new rehang opens, quite pointedly, with a painting of a detained man sitting, head bowed and wrists shackled, as he waits for the arbitrary hand of institutional bureaucracy to decide his fate.

The picture, Document No …, was painted by Juan Genovés in 1975, the year Francisco Franco died and Spain began its transition to democracy after four decades of dictatorship. Genovés’s faceless, everyman victim of the Franco regime’s control and repression is the natural starting point for the Madrid museum’s exploration of the past 50 years of contemporary art in Spain.

Through the 403 selected works, the museum’s curators examine how artists from Spain and beyond have chronicled and reacted to socio-historical changes, from the hedonistic explosion of creativity that followed the dictator’s demise to the Aids epidemic, from second-wave feminism to growing environmental awareness, and from decolonisation to global terrorism.

According to Ángeles González-Sinde, the president of the Reina Sofía’s board, the rehang – an exercise museums undertake to re-evaluate and reinvigorate their collections – is much more than a simple rejigging. Almost two-thirds of the works on display in the new Contemporary Art: 1975 to the Present collection, which occupies the museum’s fourth floor, have never been exhibited as part of the permanent collection.

“More than an exhibition reorganisation, it’s a critical reinterpretation that seeks to contextualise artistic practices in dialogue with the social, political and cultural processes that have marked these five decades,” she told a press conference on Monday.

Alongside works by internationally known artists such as Nan Goldin, Hal Fischer, Peter Hujar, Belkis Ayón and Robert Mapplethorpe are pieces that chart a rapidly changing Spanish society. The exiled Argentinian photographer Carlos Bosch used his camera to document key moments of the Transition – the process by which post-Franco Spain returned to democracy – among them Spain’s first gay pride march in 1977. The artist and queer activist José Pérez Ocaña employed altar installations to appropriate and subvert the popular rituals of Andalucían Catholicism.

The collection also features items of jewellery by the designer Chus Burés, who has created pieces for two films by Pedro Almodóvar, perhaps the most famous figures of the wild and wildly creative post-Franco underground scene known as the Movida madrileña.

The dark and destructive side of the movida is also apparent in Iván Zulueta’s 1979 arthouse horror film Arrebato (Rapture) and in the photographs of Alberto García-Alix. One of the many poignant works on show is García-Alix’s 1988 image En ausencia de Willy (Willy’s Absence), a black and white shot of a western shirt that belonged to the artist’s brother, who died of an overdose in the heroin epidemic that ravaged Spain in the 1980s. The shirt, which sits alongside a pencil sketch of Willy, serves as a potent reminder of the years when, in García-Alix’s words, “nothing was enough”.

The advent of another epidemic is memorialised in several pieces, not least in Hujar’s photographs of mummified bodies in the catacombs of Palermo, which unknowingly foreshadow the physical ravages that Aids would inflict on the artist and so many of his friends decades later.

Ajuares (Funerary Offerings), an installation by the artist, teacher and researcher Pepe Miralles, offers another musing on the epidemic by collecting together everyday objects linked to the illness and treatment of his friend Juan Guillermo. The items gathered together in a huge glass cabinet include antiretroviral medication, Prozac, gauzes, syringes, pyjamas and soft toys.

Manuel Segade, the director of the Reina Sofía, said the 403 works were intended to create a constant dialogue between the past, the present and the future.

“The Reina Sofía’s intention isn’t to create a single, unequivocal, closed narrative, but rather to open it up, to socialise these narratives as a possibility and as a way to consider this work for future presentations, so that the Reina Sofía’s collections are permanently open to revision,” he told reporters.

The fundamental aim of the three-year-long reorganisation, Segade added, was to ensure that each and every visitor could “grasp the diversity, quality and discursive potential of contemporary Spanish art and the contributions of our artists to culture in general”.

Spain’s culture minister, Ernest Urtasun, said the idea was to reflect on the “turning point” year of 1975 but also on wider questions of society, art and democracy.

Given the current state of things, he added, such reflections were as vital today as they were 50 years ago. “Just as this floor begins with Juan Genovés – with the aspirations of Spain at that time, with its social aspirations and the role that contemporary art played in shaping perspectives on the various democratic social achievements of recent years – so I believe we must also be aware of the importance that contemporary art will play in the fight for democracy and in the defence of our fundamental values, the values of the Enlightenment,” Urtasun said.