DHS has blamed local politicians and activists for inciting violence, saying attacks on officers have climbed sharply, leaving them no option other than to respond in kind. The agency points to the conduct of some protesters, who follow officers with their cars, block them in the street, curse at their faces, blow ear-piercing whistles and clamor outside their hotels at night. At times protests have turned violent, with demonstrators throwing bottles, rocks and fireworks, and officers have arrested many people for allegedly trying to assault them or hit them with cars.

DHS said in a statement that its officers “are facing a coordinated campaign of violence against them.” The agency did not answer questions about specific instances of federal officers using less lethal force on protesters. Instead, it highlighted about two dozen alleged attacks on officers. In one, an officer suffered burns and a severe cut, requiring 13 stitches, while arresting a man from El Salvador; he was charged with assault and the case is pending. In another, a woman allegedly bit off part of an officer’s finger and was charged with assault; the case is pending and her lawyer said it was “meritless.” In a third, a Guatemalan national was sentenced to prison after pleading guilty to attempting to choke officers and grabbing one by the genitals.

“Despite these real dangers, our law enforcement shows incredible restraint and prudence in their exercise of force” to protect officers and others, the statement said. DHS said that claims of misconduct are “thoroughly investigated” and acted on “as necessary” but did not provide details.

Some who go to the street to protest or record officers’ conduct know that they risk getting badly hurt.

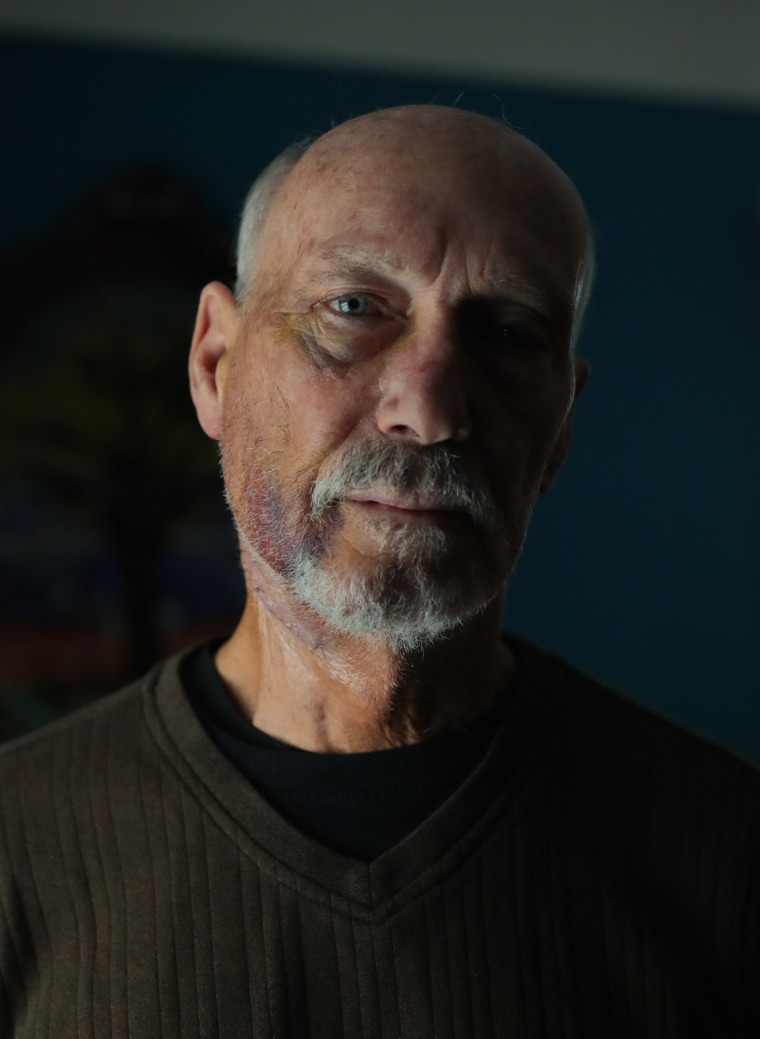

Leon Virden looked past the danger. He is 73, a lifelong Minneapolis resident who grew so upset after the Jan. 24 killing of Alex Pretti that he drove with his son to the scene. They ended up in a small group of chanting protesters in an alley where they came upon officers he believed were from DHS. One deployed a flash-bang grenade — which federal officers have used repeatedly at protests — and it exploded, shattering Virden’s face. Now he sits at home, popping Tylenol and trying not to aggravate his surgically reconstructed jaw.

“I’m really pissed off that these, you can call them anything you want, I call them agents of the Antichrist, that they can come in and do this and get away with it,” Virden said. “I’m pissed off. I hurt a bit, and I just want to see some change.”

Los Angeles: The campaign begins

The first immigration raids began in Southern California in late May, driven by Trump’s demand to detain 3,000 people a day. Masked and heavily armed federal officers, many of whom were accustomed to border patrols or targeted operations that did not typically involve tense encounters with the public, were now sweeping densely populated neighborhoods, scooping up Latino immigrants at bus stops, homeless shelters, Home Depot parking lots, farms, workplaces and homes.

The masked officers, in roving caravans of unmarked cars, drew resistance from angry crowds of immigration advocates and ordinary citizens, and were told by their leaders to meet anyone who harmed them with force.

“Arrest as many people that touch you as you want to. Those are the general orders all the way at the top,” the leader of the operation, Border Patrol commander Gregory Bovino, told agents in Los Angeles, remarks captured by a body camera and later filed in court. “Everybody f——- gets it if they touch you. You hear what I’m saying?”