Commercial space stations are rapidly moving from concept to reality. As NASA prepares for the International Space Station’s retirement around 2030, a burgeoning private orbital industry could step into its shoes.

The ISS was humanity’s only permanent outpost in space for nearly a quarter of a century, until China’s Tiangong station was permanently crewed in 2022. But the ISS is nearing the end of its planned lifespan and NASA’s been clear that it doesn’t intend to replace the space station.

Instead, the agency wants to shift from landlord to tenant, purchasing space station services from private players rather than running a facility of its own. It’s betting the private space industry can help drive down costs and accelerate innovation.

This transition would mark a fundamental shift in the economics of low Earth orbit. And the first major milestone could come as soon as May 2026, when California-based startup Vast plans to launch its Haven-1 space station.

“If we stick to our plan, we will be the first standalone commercial LEO platform ever in space with Haven-1, and that’s an amazing inflection point for human spaceflight,” Drew Feustel, Vast’s lead astronaut and a former NASA crew member, recently told Space.com.

The company has already booked its launch on a SpaceX Falcon 9, and at around 31,000 pounds, Haven-1 will be the largest payload the rocket has ever carried. But as far as space stations go, it’s fairly modest.

Roughly the size of a shipping container, the single-module station will host crews of four for up to 10 days. But the company has tried its best to make the facility more comfortable than the utilitarian ISS, with “earth tones,” soft surfaces, inflatable sleep systems, and a revamped menu for astronauts.

Though the company hopes the design will tempt some customers, the station is really a proof of concept for Haven-2, a larger modular station that Vast hopes could succeed the ISS. Haven-2 will feature a second docking port to connect with cargo supply craft or new modules.

Development of Vast’s second station relies on funding from NASA’s Commercial Low Earth Orbit Destinations program, however, the company says. Eager to spur a new orbital economy that can support its missions, the agency started the program in 2021 to fund and assist a host of startups building space stations.

The agency has paid out about $415 million in the program’s first phase to help companies flesh out their designs. But next year, NASA plans to select one or more companies for Phase 2 contracts worth between $1 billion and $1.5 billion and set to run from 2026 to 2031.

Axiom Space, one of the companies vying for this funding, plans to piggyback on the ISS to build its space station. The company will first launch a power and heating module and connect it to the ISS. The module will be able to operate independently starting in 2028. They’ll then gradually add habitat and research modules alongside airlocks to create a full-fledged private space station.

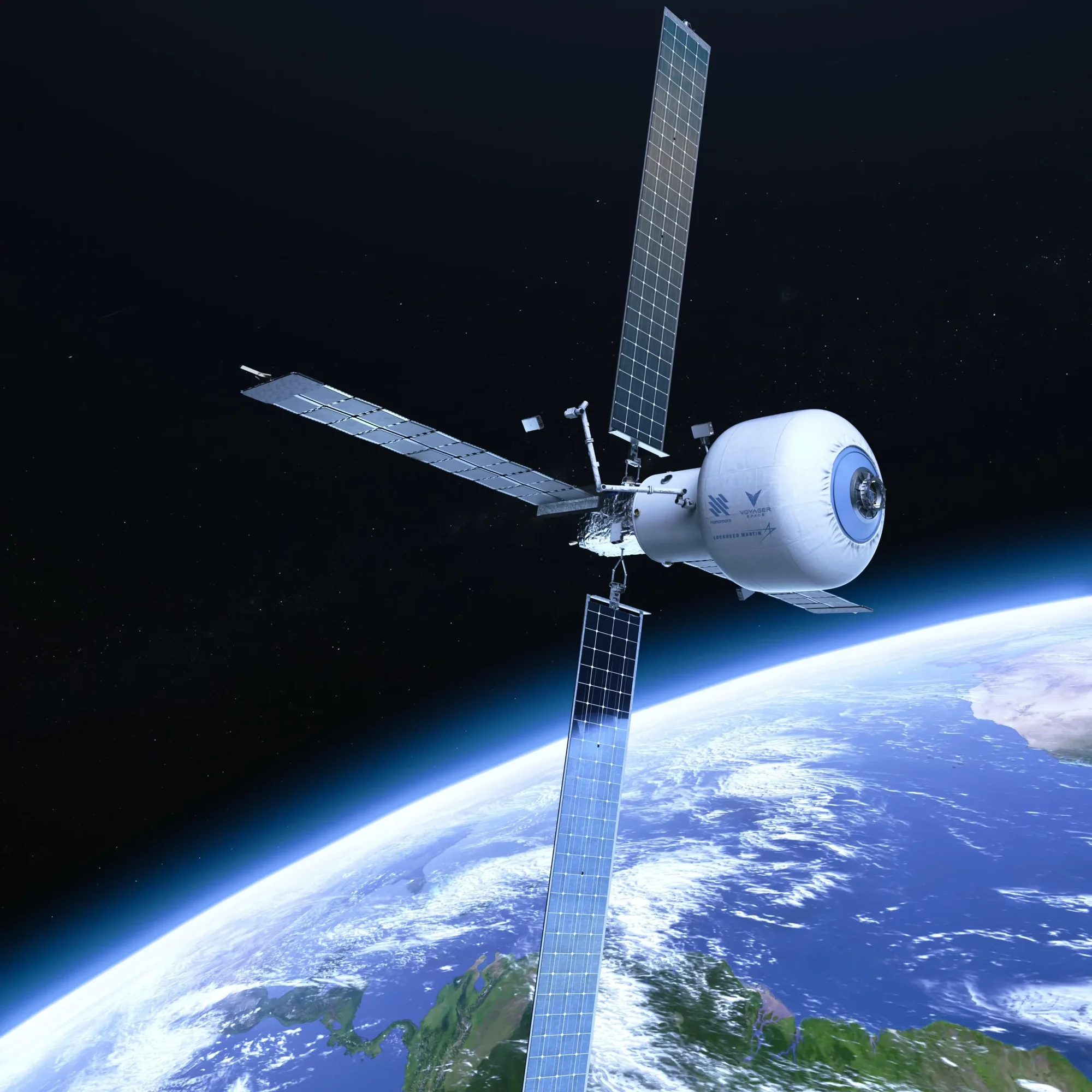

Meanwhile, Voyager Space and Airbus are designing a space station called Starlab, which recently moved into “full-scale development” ahead of an expected 2028 launch. The station can host four astronauts, features an external robotic arm, and is designed to launch in one go aboard SpaceX’s forthcoming Starship rocket.

In addition, Blue Origin, founded by Jeff Bezos, is working with Sierra Space and Boeing to build Orbital Reef, which they describe as a “mixed-use business park 250 miles above Earth.” The project recently put its designs to the test by asking people to carry out various day-to-day tasks, like cargo transfer, trash transfer, and stowage in life-size mockups of the habitat modules.

All these projects hope to have NASA as an anchor tenant. But they are also heavily reliant on the idea that there are a broad range of potential customers also willing to pay for orbital office space. With the cost of space launches continuing to fall, there’s hope that there will be ample demand from space tourists, researchers, and manufacturers eager to take advantage of the unique microgravity environments these stations can provide.

The economics are far from certain though, and competition will be fierce. Even if NASA is able to spur a private orbital economy, there may not be enough business to support multiple private space stations.

But with the sun setting on the ISS, a gap in the market is undoubtedly opening up. If things go to plan, we may soon find that humans have a lot more orbital destinations on the menu.