Patrick Condon is a Professor at the University of British Columbia. With UBC law student Thomas Kroeker, he authored The 50 Year Vancouver Experience on Housing Affordability with Adding Housing Density.

The paper is republished here with Prof. Condon’s permission.

Across North America, there is a significant movement to increase housing density in already developed neighborhoods. The underlying belief is that by increasing the housing supply, home prices will decrease and ordinary citizens will then be able to afford them. This of course aligns with the economic principle of supply and demand.

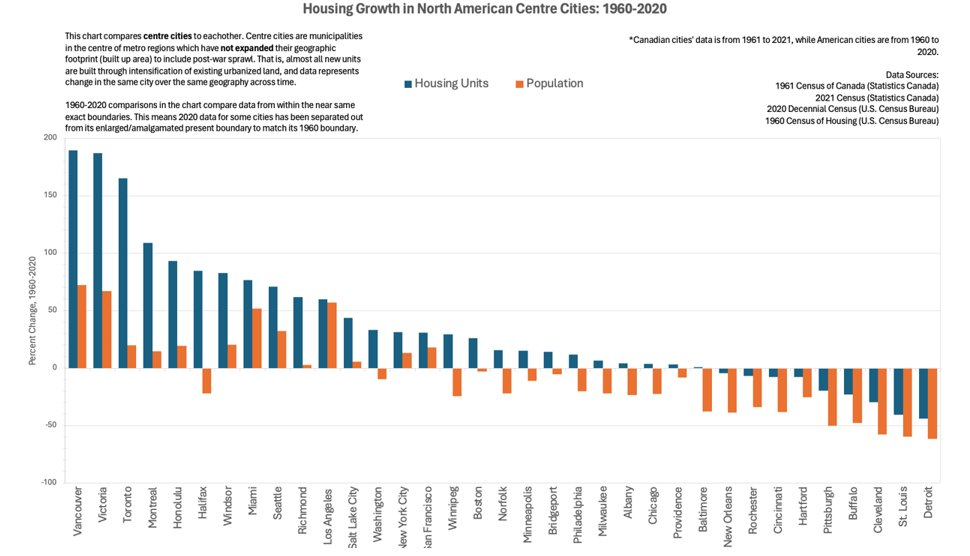

Vancouver, more than any other North American city, has, for over a half a century, actively tested this hypothesis. Since the 1960s, Vancouver has added more housing units, relative to its total housing units at that time, than any other centre city in North America. Despite this, Vancouver’s housing market is now North Americas most expensive (relative to median area household wages).

Please note that in this work we focus on already built out centre cities like Vancouver. “Centre City” refers to the main municipality at the heart of a metropolitan region (methodologies described in illustration 2).

The illustration just below shows Vancouver’s achievement relative to other North American centre cities – infilling housing units such that it nearly tripled net housing units, growing by 167 percent, against its much lower 72 percent increase in population.

The data might be better represented by showing how the ratio of housing prices to median household income has changed over time, as shown in illustration 2 below. It shows the extent to which Vancouver’s housing market has diverged from the norm in both residential density, housing unaffordability, and housing supply – all since 1960.

This raises important questions about the impact of increased housing density on home prices and, more crucially, on urban land prices.

Importantly, the substantial increase in housing units within Vancouver’s fixed geographical boundaries—thus essentially all through infill development—has not resulted in lower housing prices when compared to other major Canadian and U.S. central cities. Instead, this effort has coincided with a significant rise in the market price for developable land.

Reflecting on this data, it becomes clear that increasing housing supply does not automatically lead to lower home prices – prices that are within reach of average wage earners. Instead, the situation in Vancouver suggests a need for a more nuanced approach to understanding the relationship between housing density, land prices, and overall affordability. Ultimately, this data suggests that a strategy of nearly tripling average residential density, as Vancouver has done, does not seem to generate housing prices that are such that wage earners can afford, and that the underlying factors driving urban land price inflation are in much need of attention.

Demographics link: see attached document.