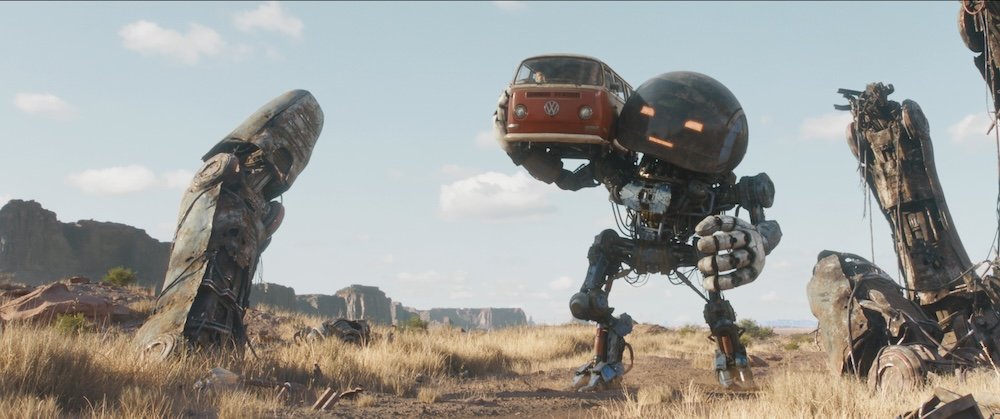

The new Netflix movie “The Electric State” depicts a world full of robots — but not robots as we know them.

Directed by brothers Anthony and Joe Russo (who previously helmed two Avengers blockbusters, “Infinity War” and “Endgame”) for a reported budget of $320 million, “The Electric State” takes place in an alternate version of the 1990s, one where sentient robots have existed for decades. That’s long enough for them to have rebelled against their human masters, lost the war, and found themselves exiled to an area of the Southwest — an area that the film’s heroes (played by Millie Bobby Brown and Chris Pratt) must sneak into.

Crucially for visual effects supervisor Matthew E. Butler, design-wise, these robots are “deliberately the antithesis” of the robots that exist today.

“Most of us have seen modern-day robots … and are used to these designs,” Butler told me. “If you look at Boston Dynamics robots, you’ll notice that they concentrate the mass of the robot at the center of the robot, and then as you go out to the extremities, they get less and less massive, because that’s just a defensible design.”

In contrast, the movie’s robot Cosmo has “a giant head on a tiny neck,” which Butler described as “the worst design for a robot.”

Like the movie itself, that design is based on Simon Stålenhag’s illustrated novel of the same name. But Butler explained that there’s an in-movie explanation for Cosmo and the other quirky robots that are often drawn from real and imagined pop culture: They were created to be “unthreatening,” which is why they all look “kind of cutesy and goofy and fun.”

All of that meant Butler’s team had to start with a design that was innately impractical but eventually create something that felt “physically believable and real.” He said that to do that, they decided to honor Cosmo’s design in “silhouette fashion.”

“If you squint and you put him a distance away from [the] camera, he looks like Cosmo, the way he is in the book,” Butler said. “But if you go up close and you scrutinize a shoulder, you’ll see that there are push rods in there, and you can see the motors, you can see the circuitry, same with the ankles and the feet.”

The goal is to convince audiences that “the thing can really work.” Once they’re convinced, they’ll accept Cosmo’s design, and the design of the other robots, without seeing all the details.

And yes, there are plenty of other robots. Butler said his team had to bring “hundreds and hundreds of unique robots” to life — unique not because every robot in this alternate world is one-of-a-kind, but because “in the movie, we typically just showcase individuals.”

And unfortunately, there were no shortcuts.

“We scratched our heads so many times — like, ‘How the hell do we do this?’” he said. “If you’ve got 100 different robots and they’re all moving, they’ve got to be able to move, which means you’ve got to be able to rig them, so someone has to design them, someone has to paint them, someone has to animate them.”

To bring those robots to life, Butler said the team used a combination of traditional optical motion capture and a newer system using accelerometer-based suits. That allowed a troupe of seven motion capture performers to work with the live action actors on location and on set, with their performance then providing the basis for the animated robots — whether they’re human-sized, gigantic, or fit into the palm of a character’s hand.

Butler emphasized that the process was far more complicated than simply transposing an actor’s movements onto a robot body.

“Take little Herman as an example,” he said. “You’ve got the [motion capture] performer, and he’s adding his flair, his performance, and it’s someone that Chris Pratt can now act with. Then you say, ‘Well, OK, but the actual robot can’t do a lot of the things that this guy can do.’ So now you need to change it based on the limitations of the design of the robot itself.”

And it’s not over yet: “And then you talk to the directors, and there’s a particular change of characteristics, which you now need to honor, so then you change that, and then you’ve got your fabulous voice actors who add so much, and now it’s like, ‘Well, if the character [sounds like] that then the cadence needs to change.’”

Butler said the robots we ultimately see on screen were created by the work of all those artists and performers coming together: “And that’s why we really just rolled up our sleeves and got on with it.”