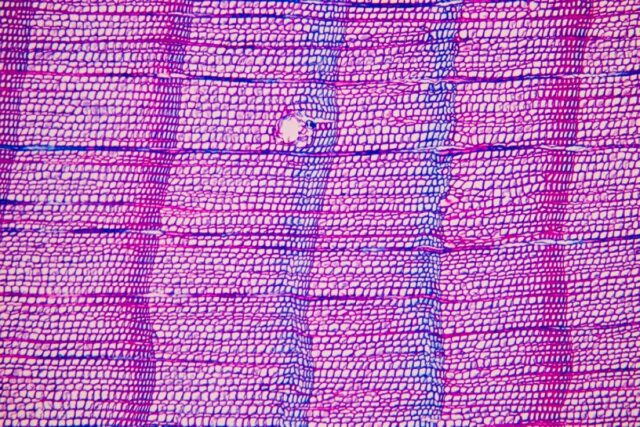

Close-up of tree ring samples taken from the Pyrenees, showing the telltale “blue rings.”

Credit:

Ulf Büntgen

The tree ring data enabled Büntgen et al. to determine that there had been a volcanic eruption (or a cluster of eruptions) around 1345, specifically so-called “blue rings” that indicate unusually cold or wet summers—in this case, for three consecutive years (1345, 1346, and 1347). The textual sources also referenced details like an unusually high degree of cloudiness and darkened lunar eclipses, indications of the after-effects of volcanic activity.

That colder climate in turn led to widespread crop failures and associated famine, particularly in parts of Spain, southern France, Egypt, and northern and central Italy. While Milan and Rome were largely self-sufficient, per the authors, smaller urban centers like Bologna, Florence, Genoa, Siena, and Venice relied on a complex grain supply system to import grain from the Mongols of the Golden Horde via established trade routes along the Black Sea coast. Textual evidence supports this, showing substantial price hikes for cereals and the imposition of grain trade regulations in 1346. This saved people from starvation but also brought Y. pestis along for the ride, with devastating consequences.

Per the authors, while the factors that triggered the spread of the Black Death to Europe are unique, the study illustrates the risks of a globalized world and calls for a similar interdisciplinary approach to future threats. “Although the coincidence of factors that contributed to the Black Death seems rare, the probability of zoonotic diseases emerging under climate change and translating into pandemics is likely to increase in a globalized world,” said Büntgen. “This is especially relevant given our recent experiences with COVID-19.”

Communications Earth & Environment, 2025. DOI: 10.1038/s43247-025-02964-0 (About DOIs).